Source: Link

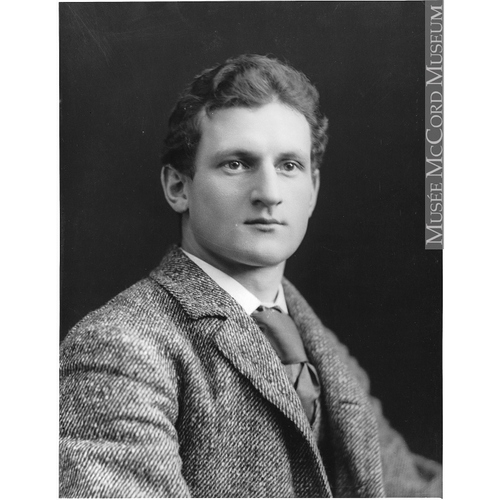

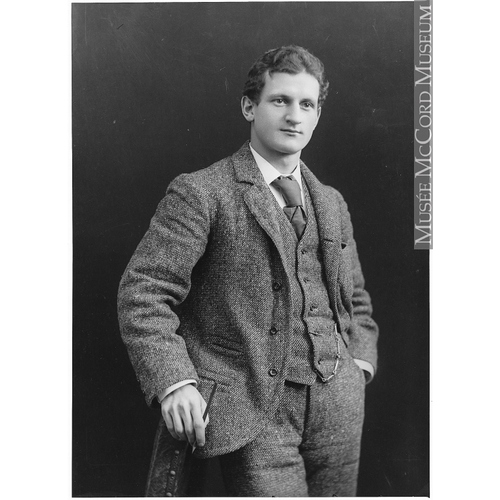

MAXWELL, EDWARD, architect; b. 31 Dec. 1867 in Montreal, son of Edward John Maxwell, a lumber dealer, and Johan Macbean; m. 15 Dec. 1896 Elizabeth Ellen Aitchison in Potsdam, N.Y., and they had four children; d. 14 Nov. 1923 in Montreal.

Edward Maxwell’s paternal grandfather was a Scottish joiner and carpenter who immigrated to Montreal in 1829. His son Edward John became a builder and in 1862 founded E. J. Maxwell and Company, lumber dealers specializing in hardwoods, a business that would remain in the family until the 1970s. Edward John’s two sons, Edward and William Sutherland, would both become architects. When Edward embarked on his career in the 1880s, there were no formal programs of study in Canada and only a handful of professional schools in the United States. Thus, after graduating from the High School of Montreal at age 14, Edward followed the traditional route by apprenticing with a local architect, Alexander Francis Dunlop. Yet apprenticeship was less than satisfactory. Speaking to fellow architects in 1891, Alexander Cowper Hutchison, a leader of the profession in Montreal, would note that “heretofore the study of architecture in any of our offices has been something of a farce.” To augment his education Edward set off for Boston, then the dominant centre for architecture in the United States. In suburban Brookline were the homes and offices of America’s most famous architect, Henry Hobson Richardson (who died in 1886), and his frequent collaborator, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. By 1888 Maxwell was working for Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge, the partnership that completed Richardson’s unfinished works. He remained there until 1891. Richardson’s influence on him was profound, as it was on countless young architects of the time.

When, in the fall of 1890, a competition was organized for the design of Montreal’s proposed new Board of Trade building, local architects were dismayed to learn that six firms from the United States had been requested to submit designs for which they would each be paid $300 expenses, but that no Canadians had been invited to participate. Those Canadians who wished to compete would not be compensated. This biased competition benefited Maxwell, for Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge received the commission and in 1891 sent him to Montreal to supervise the work. Admitted to the Province of Quebec Association of Architects that same year, Maxwell quickly caught the eye of Montreal’s powerful business elite. By the following year he had resigned from the Shepley firm and had set up his own office, although he continued to supervise the Board of Trade project. The city’s industrialists, transportation magnates, and financiers would be the mainstay of his practice until his death.

Maxwell’s first commercial building was an important one: Henry Birks’s four-storey store and office, built in 1892–94 on Phillips square in what would soon become the city’s new retail district. Not surprisingly, its design borrowed heavily from that of the Montreal Board of Trade building, which itself combined the Richardsonian Romanesque manner with Italian Renaissance influences that had gained attention in the 1880s, spearheaded by the New York firm of McKim, Mead, and White. In general, Maxwell’s commercial work of the 1890s, including the Birks store with its round-arched openings, colourful, richly-textured stone, and heavy overhanging cornice, follows the pattern learned from Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge.

William Maxwell, a gifted draftsman, gained his earliest architectural experience working in his brother’s office in the 1890s, but, like Edward, he also journeyed to Boston. Between September 1895 and May 1898 he was employed there by Winslow and Wetherel, a firm well known for its large hotels and commercial buildings, as well as for its domestic work. More important were the months commencing in the fall of 1899 that he spent in Paris with Jean-Louis Pascal, director of one of the leading ateliers associated with the École des Beaux-Arts. Before he returned to Montreal in late 1900, he had acquired expertise in the logical, systematic planning espoused by the École and in the lavish neo-Renaissance and baroque detailing that characterized current French design. He would probably also have seen art nouveau work in the decorative arts exhibits at the universal exposition of 1900 in Paris, which he attended. In 1902 William became Edward’s partner, replacing George Cutler Shattuck, who had been associated with Edward since 1899. The brothers would practise together until Edward’s death in 1923.

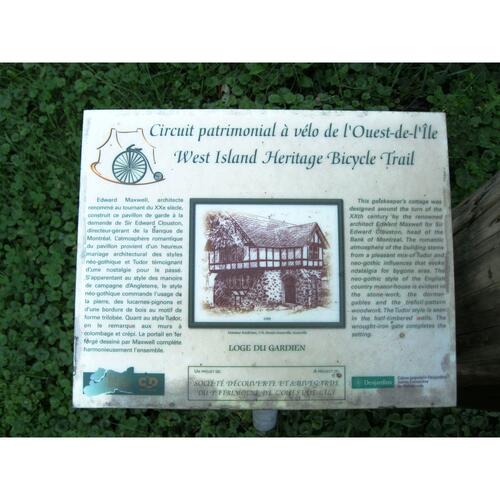

Grand urban mansions had been among Edward’s earliest commissions. Between 1892 and the onset of World War I, the firm would design more than 30 houses in the area of Montreal known as the Square Mile, where the city’s wealthiest lived, and over 20 in contiguous Westmount, where the brothers had grown up. Stylistically these homes reflect the changing fashions that appealed to some of Canada’s richest men, such as the Château-style house (1893–94) of Edward Seaborne Clouston*, general manager of the Bank of Montreal, the Queen-Anne mansion (1894) of his successor, Henry Vincent Meredith, and the opulent French neo-baroque pile (1901–2) of Charles Rudolph Hosmer, manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s telegraph system.

Reflecting their owners’ admiration of high-style homes in Boston and New York, these Maxwell houses are important not only as social records but for their craftsmanship. The Maxwell firm was an important patron of local artists, artisans, and suppliers who could provide the interior and exterior ornamentation demanded by affluent clients. Indeed, like the New York firm McKim, Mead, and White, the Maxwells were frequently required to supply furniture, wallcoverings, carpets, and even antiques to decorate the rooms they designed. The respected Montreal firm of Castle and Son provided stained and leaded glass, fine cabinetry, and interior furnishings. One of England’s leading groups of craftsmen, the Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Arts, would open an office in Montreal in 1911, followed by a workshop, thanks in part to these architects’ patronage.

Both Maxwell brothers were closely tied to Montreal’s artistic community. Edward was a long-time member of the Art Association of Montreal, in company with many of his wealthy clients. William belonged to the Pen and Pencil Club of Montreal and the Canadian Handicrafts Guild. He helped to found the Arts Club of Montreal in 1912, served as its first president, and fitted up its premises. Two of the club’s members, painter Maurice Galbraith Cullen* and sculptor George William Hill*, were among the brothers’ close friends. Hill had collaborated with the Maxwells from 1894 and he would continue until World War I, providing exterior sculpture and woodcarving and furniture for interiors. Both Maxwells were elected members of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, Edward in 1908 and William in 1914, and participated in its exhibitions (showing architectural designs and watercolours). They would serve on the academy’s council, Edward in 1910–12 and 1915–20 and William in 1916–18, 1921–23, and 1926–37.

There were many houses, large and small, which the Maxwell firm designed as vacation homes. Some, such as those for stockbroker Louis-Joseph Forget* and CPR financier and banker Richard Bladworth Angus, dating from just before and after 1900, were among Canada’s grandest country estates – modelled, as was the most opulent of American examples, George Washington Vanderbilt’s Biltmore in North Carolina, on the chateaux of the Loire. Like Biltmore, both Canadian projects involved landscape designs from the Olmsted firm of Brookline. Both estates were located on the rural western tip of the island of Montreal. Other, less ostentatious houses were designed for sites in the Laurentians, some in the rustic Adirondack style that had developed earlier in northern New York State. Seaside houses in such fashionable watering places as St Andrews, N.B., show the influence of the American shingle style of Richardson and his followers.

One of the handsomest structures designed by Edward for a seaside estate is a splendid barn for CPR president Sir William Cornelius Van Horne* situated on Ministers Island, near St Andrews. There, Van Horne kept a prize herd of Dutch Belted cattle. The barn has remarkable timber framing in addition to its fine exterior of wood and fieldstone. Van Horne, an amateur architect, may have assisted Edward; he had certainly begun designing the house on his estate, but had ultimately called on Edward to help him, perhaps with the original building and certainly with several additions from 1899 onwards. Edward must have admired the dynamic Van Horne, for he built himself a country retreat on 160 acres he purchased in 1908 in Baie-d’Urfé on the island of Montreal; there he kept a choice herd of Jersey cattle. Like many of his clients, he also had a summer home in St Andrews. Tillietudlem was constructed around 1900. Again like so many of their clients, both brothers owned homes in Montreal’s Square Mile, which they designed themselves.

Edward’s skills as an architect were especially appreciated by the men who directed the CPR and its related enterprises. The CPR had become a client in 1897, when Edward had been asked to complete a grand western terminus in Vancouver for the transcontinental railway. Three years later he designed a large addition to the CPR’s headquarters, Windsor Station, in Montreal. Over the years the firm would design stations and hotels across the dominion which would be landmarks in their time. Among the most notable are the station in Winnipeg and its accompanying hotel, the Royal Alexandra (1904–06), the 350-room Palliser Hotel (1911–14) in Calgary, and the central tower and additional wings (1920–24) that transformed the Château Frontenac in Quebec City into a Canadian icon. For the additions to the Château, the Montreal branch of the Bromsgrove Guild would later advertise that it had provided “all the modelling for all ornamental work in wood, iron, bronze, plaster and stone . . . as well as many items of special furniture.”

These stations and hotels had followed the shift in design that had been evident in the firm’s output as a whole, from Edward’s late-Victorian picturesque work inspired by the New England stations of Richardson and his successor, Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge, to the confident beaux-arts classicism that William had introduced when he became a partner in 1902. Railway commissions had helped raise the status of the Maxwell office across Canada, but the advent of William as a partner had also been important, bringing expertise in newer fashions and design that ensured the firm’s continuing success throughout the first quarter of the 20th century. Art nouveau seems to have been too extreme for the Maxwells’ conservative clientele for there is only the slightest trace of this fashion in the odd, sharply pointed dormers and segmental arched window heads and main entrance of the Angus country house in Senneville (1902–3) or in the sophisticated townhouse (1907–8) designed for Richard Ramsay Mitchell in Westmount. Interestingly, the most conspicuous example of this fashion, a proposal dated 1903 for a mansion in Montreal for John Kenneth Leveson Ross, son of the CPR contractor James Ross*, was rejected in favour of the stately exercise in neo-baroque classicism that was built in 1908–9 and which resembles the end pavilions of the Saskatchewan Legislative Building (1908–12) in Regina, also designed by the Maxwells.

William’s beaux-arts approach served the firm well as it entered numerous competitions and dealt with important and complex commissions in the 20th century. In 1907 the Maxwells won the competition, open to all Canadian architects, for the Justice and Departmental buildings in Ottawa. Although their scheme was never built, the project enhanced their reputation. Their prestige was further augmented a year later when their design for the Saskatchewan Legislative Building was chosen in a limited, international competition. This major success was quickly followed by another: their winning design for a new gallery for the Art Association of Montreal (later renamed the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) (1911–12). Other notable works in Montreal during this period were the Church of the Messiah (1906–8) and the High School of Montreal (1912–14). The last great project the two brothers undertook together, the enlargement of the Château Frontenac, completed a year after Edward’s death, marked a summation. While maintaining the picturesque chateau mode of the original building, the new work benefited from the two great axes of its plan, which gave a classical order to its varied parts, a perfect melding of the two Maxwells’ talents.

Following Edward’s death, Gordon MacLeod Pitts, an architect in the Maxwell office, became William’s partner. The firm soon lost momentum, however. The brothers had complemented each other, not only as architects, but also as personalities. William was the more reserved, happiest in the company of artists, while Edward had been skilled at business and had pursued an active social life. In 1940 William moved to Haifa (Hefa), Israel, to be with his only child, Mary Maxwell Rabbani, who had married the head of the Baha’i faith. There, he designed his most unusual building, the gold-domed superstructure (1948–53) for the Shrine of the Bab, a major pilgrimage site for Baha’is around the world. Spectacularly sited on the slopes of Mount Carmel, the arcaded, marble and granite structure was a fitting conclusion to his career, epitomizing grand beaux-arts design. In 1951, suffering from ill health, he returned to Montreal and died there the next year.

The Maxwell office had been one of the most important in the history of Canadian architecture. Although they came to their profession at a time when Canadian architects lacked adequate training opportunities and status, the two brothers created the largest and most successful firm in the country during the early part of the 20th century. They kept abreast of change, providing clients with a variety of building types in a range of fashionable styles. Edward’s business and organisational abilities enabled the office to grow and handle large commissions, while William’s collegiality and atelier experience made it an important and effective training place. Among the draughtsmen who would later become respected Canadian architects were John Smith Archibald*, David Robertson Brown, David Huron MacFarlane, Kenneth Guscotte Rea, and Charles Jewett Saxe. Not only did Edward and William Maxwell themselves benefit from their success, but so, too, did the Canadian profession as a whole.

The papers of Edward Maxwell, his brother William Sutherland, and their various partnerships are held in the John Bland Canadian Architecture Coll. of the Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill Univ. Libraries (Montreal), Acc. no.2. They contain documentation for over 700 projects and include more than 16,200 plans and drawings, as well as personal correspondence, business papers, journals, notebooks, scrapbooks, clippings, photographs, fabric swatches, and artefacts. Significant new material has been added to the collection since the publication of Edward & W. S. Maxwell: a guide to the archive, ed. Irena Murray (Montreal, 1986). Throughout their lives, both Maxwells were avid book collectors, especially of works on art and architecture, including rare or limited editions. William’s collection alone is thought to have totalled between 3,500 and 4,000 volumes. Part of the collections have been preserved and are listed in The libraries of Edward et W. S. Maxwell in the collection of the Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art, McGill University, comp. Cindy Campbell et. al., intro. Irena Murray (Montreal, 1991). Numerous archival documents, photographs, and essays on the Maxwells have been placed on the Web as part of the digital collection “The architecture of Edward and W. S. Maxwell: the Canadian legacy” at http://cac.mcgill.ca/maxwells/.

ANQ-M, CE601-S126, 30 avril 1861. BCM-G, RBMB, Knox Presbyterian Church (Montreal), 9 Jan. 1869. Gazette (Montreal), 14–15 Nov. 1923. Montreal Daily Star, 14 Nov. 1923. The architecture of Edward & W. S. Maxwell (exhibition catalogue, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1991). Kelley Crossman, Architecture in transition: from art to practice, 1885–1906 (Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1987). France Gagnon-Pratte, Country houses for Montrealers, 1892–1924: the architecture of E. and W. S. Maxwell (Montreal, 1987). R. M. Pepall, Montréal, 1912: building a beaux-arts museum (exhibition catalogue, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1986). “Province of Quebec Association of Architects,” Canadian Architect and Builder (Toronto), 4 (1891): 88, 90–91. Royal Canadian Academy of Arts; exhibitions and members, 1880–1979, comp. E. de R. McMann (Toronto, 1981). The storied province of Quebec; past and present, ed. William Wood et al. (5v., Toronto, 1931–32).

Cite This Article

Susan Wagg, “MAXWELL, EDWARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maxwell_edward_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maxwell_edward_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Susan Wagg |

| Title of Article: | MAXWELL, EDWARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |