Source: Link

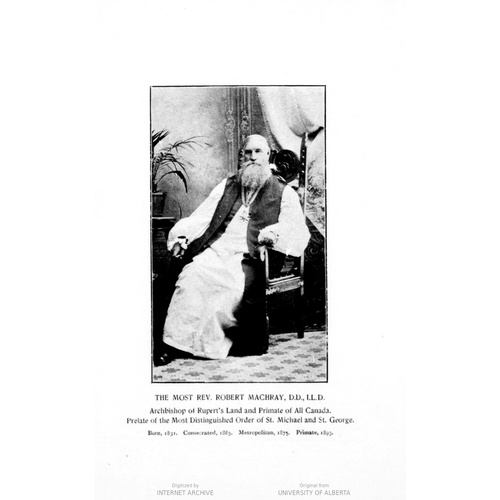

MACHRAY, ROBERT, Church of England clergyman, archbishop, and educator; b. 17 May 1831 in Aberdeen, Scotland, son of Robert Machray, an advocate, and Christian Macallum; d. unmarried 9 March 1904 in Winnipeg.

Robert Machray was born into a middle-class professional family whose members were ardent Presbyterians. Following his father’s death in 1837, he was sent to live with his father’s half-brother, Theodore Allan, a parish schoolteacher. Living with his uncle contributed to Machray’s lifelong interest in education. It also gave him the opportunity to see firsthand the bitter divisions in the Church of Scotland between adherents of the Kirk and their opponents in the Free Church. Machray’s family were divided on the issue. Most were active supporters of the Free Church while Allan, although sympathetic, continued to follow the Kirk. Young Machray evaluated the issue independently and rejected both sides. No doubt affected by the Tory views and Episcopalian traditions of his mother’s family, he eventually turned to the Episcopal Church in Scotland and its parent church, the Church of England. He continued to attend the Presbyterian Church but resolved to become an Anglican when such a move became feasible.

Machray studied mathematics at King’s College, Aberdeen, and at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, graduating with an ma from King’s College in 1851 and a ba from Sidney Sussex in 1855. He then won a fellowship at Sidney Sussex which entitled him to pursue holy orders. He was deaconed in 1855 and ordained, probably on 9 Nov. 1856, by the bishop of Ely, who had confirmed him in the Church of England four years earlier. After a brief period as a tutor in Rome and on the Isle of Man, Machray returned to his studies at the University of Cambridge, eventually earning an ma in mathematics.

In 1859, shortly after receiving this degree, Machray was appointed dean of Sidney Sussex College. The position, along with the award of the vicarage of Madingley, meant that he was secure for life, both socially and financially. He gave up his comfortable existence after six years, however, when the Church Missionary Society recommended him as a replacement for Bishop David Anderson*, who had retired from the bishopric of Rupert’s Land. A logical choice for the position, Machray had impeccable credentials, both as an evangelical and as an administrator. Unlike many of the missionaries sent by the CMS to Rupert’s Land, he was a recognized scholar with a well-established social position. On 24 June 1865 he was ordained at Lambeth Palace. At 34, he was the youngest bishop in the church at the time.

The diocese of Rupert’s Land in 1865 covered the entire territory of the Hudson’s Bay Company east of the Rocky Mountains. Machray therefore presided over the activities of his church in an area now comprising the Prairie provinces, the Yukon Territory, most of the Northwest Territories, northern Ontario, and northern Quebec. There were missions in the Yukon, on the Mackenzie River, and at Fort Albany, Moose Factory, and English River (Ont.), as well as at York Factory (Man.). The bulk of the settled parishes were within the Red River colony (Man.) and it was there that most of the 22 clergy in the diocese were located.

Machray travelled to the Red River colony through the United States. There, he consulted with several American prelates, including the bishop of Minnesota for the Protestant Episcopal Church, Henry Benjamin Whipple, a friend from his days at Cambridge. Machray stayed in close contact with the American church and learned of its experiences during the rapid settlement of the American west. He fully anticipated that Rupert’s Land would soon be transferred to the Canadas, with a resulting influx of settlers on a scale similar to that experienced by the United States. The American bishops confirmed his fears that his church would be unable to meet the demands of an increased population unless it was well prepared. Machray was particularly concerned about the possible erosion of the spiritual and secular authority of the Church of England as other churches grew and asserted themselves.

Frits Pannekoek has identified Machray’s arrival in Red River as marking the end of the mission church and the beginning of the settlement church. In many ways this is an accurate assessment since Machray immediately began to restructure the work of the church in the diocese to prepare for the coming transfer. His first task was to make the settlement church self-sufficient. Before he left England, the CMS had informed him that the costs of ministering to the settled parts of the diocese would have to be shifted from the society to the settlers themselves, so that the resources of the CMS could be devoted to mission work. In order to lessen the immediate impact of this decision, the CMS agreed to reduce its support gradually over five years.

Machray reorganized the church in Rupert’s Land to meet his own vision of its key role within a British and conservative society. He sought to improve its efficiency and to make it more responsive to the needs of the people it served by decreasing its emphasis on personal piety and strengthening it as a community. In preparation for the establishment of a permanent diocesan synod, he called a meeting of the clergy and laity of the diocese in May 1866. The synod, which first met three years later, would prove to be an effective means of giving the laity a sense of involvement with the work of the church, thus encouraging them to support it financially. He also introduced the elected vestry as the main focus of parish organization and he initiated a regular offertory in order to make individual parishes self-sufficient. Machray re-created the Church of England’s system of parish schools, building a school in every parish in the colony by 1869. With the help of his friend the Reverend John McLean* he reopened St John’s College in 1866 to offer higher education and to train promising individuals for the priesthood. He was a professor there from 1866 until his death, with the exception of two brief periods in 1883 and 1890. Although he held the chair of ecclesiastical history from 1866 to 1883, he actually taught a variety of subjects during and after that period.

On a more controversial note, he had decreed in 1865 that the services of the Church of England should conform to the Book of Common Prayer and that Presbyterian practices, traditionally tolerated in the colony, should be eliminated from the church. Although his decree earned him the charge of high churchmanship from evangelical clergymen, he dismissed these critics with the argument that there was no better way to worship God than in the manner prescribed by the Church of’ England. His actions caused some enmity within the church in the short term, but they eventually benefited it. Stressing the church’s unique services and practices distinguished it from the other Protestant churches and helped to build a strong sense of identity.

Machray also reorganized the native missions, long in disarray under his predecessor. It was his intention someday to create an indigenous church with Europeans acting only as supervisors. Meanwhile, he tried to place more of his experienced missionaries in the field and enraged some when he ordered them from their comfortable berths at Red River to outlying mission stations. He lamented the lower pay that native missionaries such as Henry Budd* and James Settee were forced to accept from the CMS, and he criticized British missionaries for treating them as inferior. He never succeeded in creating a native clergy on any significant scale; missions and residential schools [see Allen Patrick Willie*] continued to be manned primarily by Europeans. Like other missionaries, he failed to comprehend that, for potential indigenous missionaries, inclusion in the church required cultural assimilation as well.

From Machray’s perspective, the announcement in 1869 that Canada was to have jurisdiction over Rupert’s Land could not have come at a better time. The revenues he was raising locally had not yet caught up to the expenses of running the settled diocese and a larger base of parishioners would no doubt be helpful. In a letter to the secretary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in 1869 he expressed his concerns about how the church would fare. “The early tide of Emigration has never been found favourable for the Church. There are ordinarily [few] Churchman among [the settlers] and there is a wild feeling that rebels against the decorum and order of the church.” He hoped for financial help from the church in Canada, but pessimistically expected “opposition and difficulties.” “It will be hard if our Church there gives no aid.”

Machray recognized that there was disquiet in the community about the transfer, particularly among the Métis. In 1868, immediately after hearing that negotiations had begun, he had written to the colonial secretary, the Duke of Buckingham, requesting that the government clarify the titles of squatters and that a small detachment of soldiers be sent to maintain the peace. No action was taken. When the provisional government of Métis leader Louis Riel* seized control of Red River in December 1869, Machray blamed the Canadian government for not having prepared the colony properly or consulted with local leaders. He also condemned the surveyors under John Stoughton Dennis* who had not shown proper respect for the concerns of the colonists and the members of the Canadian party, such as John Christian Schultz* and Charles Mair*, who had misled the Canadian government about the true condition of the colony.

Although sympathetic to the Métis’ grievances, Machray had reacted negatively to their taking up arms. He advocated the use of force to suppress the uprising and bitterly criticized its supporters. When it became clear, however, that the Métis were too powerful, he worked to have the more hot-headed members of the English-speaking community lay down their arms. He participated in the negotiations over the establishment of the provisional government, acting as a representative of the English community, but at the same time wrote letters to the government of Canada urging it to take action to quell the uprising. When the troops led by Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley* made their way to Red River, Machray sent guides to Rat Portage (Kenora, Ont.) to show them the way to the colony.

Machray’s actions in the resistance are a point of minor historical controversy. A contemporary, Alexander Begg*, painted him as a peacemaker who suggested reasonable courses to both Riel and his opponents as well as a significant calming force during the dispute. This view influenced others, most notably historian William Lewis Morton*. More recently, Pannekoek has painted a different picture of Machray as a jingoistic agitator arguing for violent suppression of the Métis and counselling the laying down of arms only when he was certain that an outside force would arrive. At the same time he was deceptively presenting himself as a diplomat. For Pannekoek, Machray was motivated by a combination of anti-Catholicism and contempt for the colony and its inhabitants.

The truth likely lies somewhere in between. Machray had no trouble with the use of violence to put down the provisional government, but there is no evidence to suggest that he was opposed to a peaceful solution. As to his motives in opposing the uprising, although Machray distrusted the Roman Catholic Church on principle and looked to Canada as the future of Rupert’s Land, neither anti-Catholicism nor contempt for Red River was sufficiently strong in him to explain the forceful stand he took in 1869–70. He hated the resistance for two reasons. As a conservative, he rejected the taking up of arms against the crown for any reason. Perhaps more important, he feared that the Métis would be exploited by forces opposed to the British empire, particularly American expansionists or Fenians [see William Bernard O’Donoghue*]. The result would be the annexation of Red River and the loss to Britain of a valuable place to send its poor. His vision for the future of the territory included neither self-determination for the Métis nor their eradication.

In the 20 years following the resistance, the diocese of Rupert’s Land changed dramatically and the Church of England adapted to its needs. In 1872, several years after Machray first suggested the idea, he was allowed to divide his diocese. The CMS provided funds for the establishment of the dioceses of Moosonee and Athabasca; John Horden* and William Carpenter Bompas were appointed bishops in 1872 and 1874 respectively. The SPG promised to assist the diocese of Saskatchewan, of which Machray’s friend McLean was consecrated bishop in 1874. Machray remained as bishop of a much smaller diocese of Rupert’s Land, comprising what is now southern Manitoba, northwestern Ontario, and part of southeastern Saskatchewan; his former diocese became the ecclesiastical province of Rupert’s Land in 1875, and he was appointed its metropolitan. He had added the duties of warden of St John’s College when McLean left the post to become bishop.

New parishes were started, missions expanded, and residential schools opened as the church struggled not only to meet the needs of the residents but also to compete with the other denominations. The pressures of reorganization and growth, coupled with disruptions resulting from the resistance, led to continued financial hardship for the church. Conflicts with the Hudson’s Bay Company over its reduction or elimination of certain grants and over the trust left by James Leith* added to the church’s problems. The hoped-for funding from central Canada did not materialize and Machray was forced to make several trips to England to raise funds. For the rest of his life the single greatest pressure on him was finding sources of revenue.

Politically, Machray wielded less direct power after 1870 than before. He had been appointed as a matter of course to the Council of Assiniboia on his arrival in Rupert’s Land, but the new political structures of the province of Manitoba had no official role for him. He did, however, exercise considerable influence as chairman of the Protestant section of the Board of Education, a position he held from the board’s inception in 1871 to its abolition in 1890. The Protestant section of the dual public school system had been created mainly from the old Anglican parish school system, and Machray helped to direct the education of all Protestant children in Manitoba. He also served as chancellor of the University of Manitoba, an institution he was instrumental in founding [see Alexander Morris*], from its beginning in 1877 until his death in 1904.

Two issues dominated the later years of Machray’s episcopate. The first was the creation of a national body for the Church of England. Prior to 1893 the ecclesiastical provinces of Rupert’s Land and Canada, and the dioceses of British Columbia, New Westminster, and Caledonia in the province of British Columbia, were autonomous units, responsible directly to Britain, with no formal connection to each other. Machray and others advocated the forming of a general synod to coordinate the church’s resources in Canada and to allow the church to speak with one voice. In 1890 Machray hosted a conference in Winnipeg of representatives of the two ecclesiastical provinces and the diocese of New Westminster, and an agreement on a new church hierarchy was reached. In 1893, at the first meeting of the General Synod of the Church of England in Canada, he was chosen first primate of Canada with the title archbishop of Rupert’s Land.

The second issue was the struggle against what he perceived to be the gradual secularization of society, particularly in the school system. When, in 1889, the provincial government of Thomas Greenway announced its intention to eliminate the dual public school system of the province and replace it with a system of non-denominational schools, Machray was outraged and threatened to re-establish the Anglican system of parish schools. He became an ardent critic of the government’s policy both during and after the crisis, which became known as the Manitoba school question. The issue revealed just how much his church had changed in the intervening period, for the government’s policy found support amongst the church’s laity. The synod was thus paralysed and the church prevented from becoming a significant force in the debate. Machray’s influence was further undermined by his decision to accept the chair of the Advisory Board established to assist the Department of Education. Although he realized that by accepting the post he was supporting the new system, he believed that he could have a greater impact on the system from within and bowed to public pressure to accept the post. Another factor in lessening his influence was his public humiliation when he learned that Hector Mansfield Howell*, his chancellor as bishop and his personal lawyer, had manipulated him to aid the government’s cause in the case of Logan v. the City of Winnipeg [see Greenway]. Believing the case to be a legitimate challenge to the new system by a member of his church, Machray had been persuaded by Howell to support it. His efforts to distance himself when it was revealed that the case had been brought to the courts to undermine the arguments of Roman Catholics [see John Kelly Barrett*] came too late to have any impact.

Machray received many honours in his last years. On 9 March 1893 he was appointed a prelate of the Order of St Michael and St George by the British government for distinguished service to the empire. Several universities gave the ageing archbishop honorary doctorates, adding to the dd Cambridge had bestowed on him in 1865. His last years were plagued by ill health as he continued to fulfil the duties of his many offices. In 1903 Samuel Pritchard Matheson* was appointed suffragan bishop to help him administer the diocese. After his death Machray lay in state at the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba on 11 March, honoured for his services to the province, before his burial in the cemetery of St John’s Cathedral the following day.

Robert Machray can be summed up as a man who made up his own mind and then was not easily dissuaded from his course. His courageous actions in choosing a church, during the Riel resistance, and throughout the Manitoba school question all point to someone who was willing to stand alone if necessary in order to achieve what he believed to be correct. His conviction was in many ways an admirable quality; however, it can now be seen that his uncritical faith in his own views had devastating results in some areas. His support for residential schools and his rejection of distinctive rights for the Métis hardly made him unique and were reflections of the society in which he lived, but his intransigence in these matters had serious consequences. Machray brought to his church a superb organizational ability and a clear understanding of what was needed to prepare it for the changes facing the west after 1870. His contributions to Manitoba included his dedication to public education, which considerably furthered the development of schools at all levels, and his own presence as an unchanging figure in what was otherwise a chaotic world.

NA, MG 17, B2, C, C.1; G, C.1 (mfm.). PAM, P 339/PRL-84-7; P 348–49/PRL-84-36; P 350–54/PRL-84-37; P 366–70/PRL-84-82. T. C. B. Boon, The Anglican Church from the Bay to the Rockies: a history of the ecclesiastical province of Rupert’s Land and its dioceses from 1820 to 1950 (Toronto, 1962). W. J. Fraser, St. John’s College, Winnipeg, 1866–1966; a history of the first hundred years of the college (Winnipeg, 1966). Christopher Hackett, “The Anglo-Protestant churches of Manitoba and the Manitoba school question” (ma thesis, Univ. of Man., Winnipeg, 1988); “The Church of England and the Manitoba school question,” The Anglican Church and the world of western Canada, 1820–1970, ed. Barry Ferguson (Regina, 1991), 94–103. R. C. Johnstone, “Robert Machray,” Leaders of the Canadian church, ed. W. B. Heeney (3 ser., Toronto, 1918–43), 2nd ser.: 179–200. Robert Machray, Life of Robert Machray, d.d., ll.d., d.c.l., archbishop of Rupert’s Land, primate of all Canada, prelate of the Order of St. Michael and St. George (Toronto, 1909). Frits Pannekoek, A snug little flock: the social origins of the Riel resistance of 1869–70 (Winnipeg, 1991). L. F. Wilmot, “Robert Machray and the foundation of the University of Manitoba in 1877,” The Anglican Church and the world of western Canada, 1820–1970, 83–93; “Robert Machray – missionary statesman,” Man., Hist. and Scientific Soc., Papers (Winnipeg), ser.3, no.13 (1957–58): 48–59 (repr. as Canadian Church Hist. Soc., Offprint (Toronto), no.12 (November 1958)).

Cite This Article

Christopher Hackett, “MACHRAY, ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/machray_robert_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/machray_robert_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Christopher Hackett |

| Title of Article: | MACHRAY, ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |