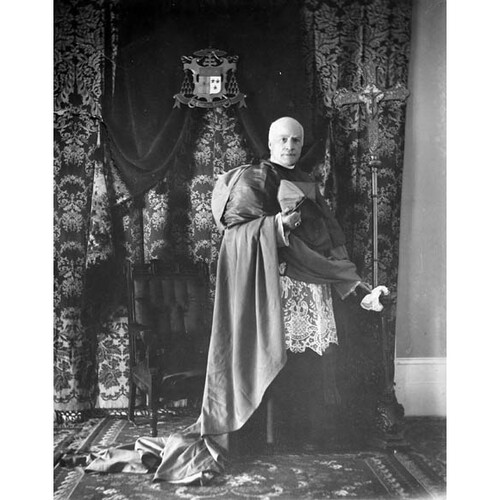

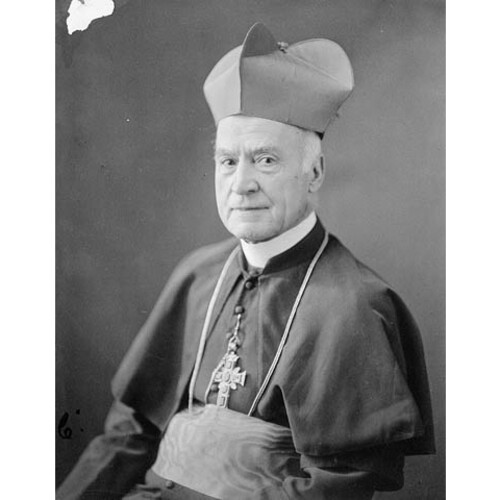

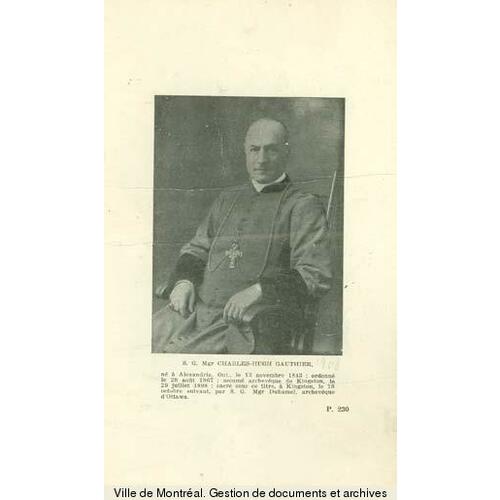

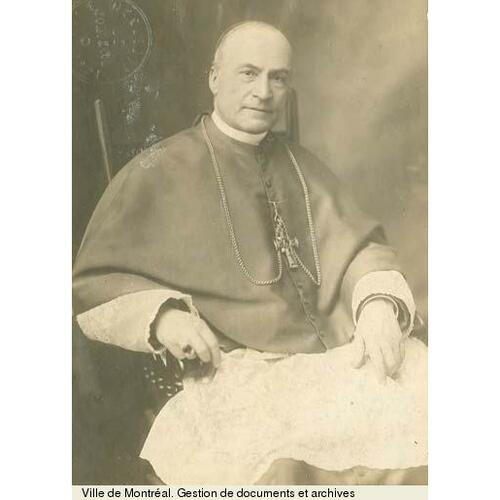

GAUTHIER, CHARLES HUGH, Roman Catholic priest, professor, and archbishop; b. 13 Nov. 1843 in Alexandria, Upper Canada, son of Gabriel Gauthier, a farmer, and Mary McKinnon; d. 19 Jan. 1922 in Ottawa.

Of French Canadian and Scottish parentage, Charles Gauthier received his early education from the Brothers of the Christian Schools in Alexandria. Later he attended Regiopolis College in Kingston, from which he graduated with high honours in 1863; he subsequently studied theology at the Grand Séminaire in Montreal. On 24 Aug. 1867, at St John the Baptist Church in Perth, Ont., he was ordained by Bishop Edward John Horan* of Kingston. He served as professor of rhetoric and director of Regiopolis College until 1869, when Horan made him pastor of St John the Evangelist parish in Gananoque, a charge that included missions at Howe Island, Lansdowne, Jones Falls, and Brewers Mills. In 1875 he was transferred to Westport and then, upon the accession of Bishop John O’Brien, to St Mary’s parish in Williamstown. He spent 11 years there, during which time he opened a new parish at nearby Glen Nevis (which he also administered), constructed a new rectory in Williamstown, built mission churches in Lancaster (1885) and Martintown (1886), and liquidated the debt of St Mary’s. Moved to Brockville in 1886, he acted as regional dean and, after 1891, as vicar general for the archdiocese of Kingston. His fluency in English, French, and Gaelic enabled him to communicate with its principal linguistic groups.

Gauthier’s pastoral skills, good humour, and financial acumen were acknowledged by his fellow priests when, in an unprecedented step, 37 of them met and selected him as their choice to succeed Archbishop James Vincent Cleary*, who had died in February 1898. Kingston’s clergy were fearful that the Vatican might appoint the bishop of Waterford and Lismore, in Ireland, to succeed the Irish-born Cleary, instead of a Canadian who understood the diocese and its needs. Their petition may have influenced the Canadian bishops’ recommendation to Pope Leo XIII, who named Gauthier archbishop on 29 July. He was consecrated in Kingston on 18 October.

Like the priests who supported him, many Kingstonians regarded Gauthier as moderate in both politics and temperament – a striking contrast to his predecessor. “The choice of Msgr. Gauthier has been hailed throughout the country, as a special grace of divine Providence,” exclaimed Archbishop Joseph-Thomas Duhamel* of Ottawa. “For me, I consider it a gift of God.” The new archbishop continued the energetic pace he had set as a parish priest. Within his diocesan boundaries, which extended west from Dundas County to just beyond the Trent River and from Lake Ontario to Algonquin Park, he administered 41,384 Catholics, who constituted 16 per cent of the diocese’s entire population. His frequent travels throughout the diocese and familiarity with its growing towns and villages made it easier for him to approve the construction of new churches and rectories, and renovations of ageing ones, in such centres as Odessa (1898), Ormsby and South Mountain (1899), Lombardy (1900), Frankford (1901), Lansdowne (1901), Merrickville (1902), Lanark (1903), Marmora (1904), Toledo (1907), and Enterprise (1908). His episcopate was also marked by the construction of St Francis’ Hospital in Smiths Falls, St John’s Convent in Perth, and St Mary’s of the Lake Orphanage in Kingston, and renovations to Kingston’s Hôtel Dieu hospital.

Gauthier’s Kingston years were devoid of the sectarian tension that had earned the city the nickname the Derry of Canada [see John Gaskin*]. His own actions won him respect among its Protestants. When St George’s Cathedral was gutted by fire in 1899, for example, he was one of the first to offer sympathy and financial aid to Anglican archbishop John Travers Lewis*. Although he contributed to the atmosphere of toleration and commented on the absence of Protestant proselytizing in his diocese, he still worried that local Catholicism was being endangered by mixed marriages, increased socializing with Protestants, and Catholic attendance at public schools. For Gauthier, the establishment of Catholic schools “wherever possible” was the surest way to strengthen the Catholic minority in a largely Protestant province. In 1901, 4,000 out of 6,000 Catholic children of school age were enrolled in the diocese’s separate schools; the remaining 2,000, according to Gauthier, lived in areas with no access to Catholic schools. By the end of his tenure new ones had been created in Belleville, Tweed, and Chesterville.

His interest in separate schools extended beyond his diocese. He quickly became a respected leader among the bishops on the issues of teachers’ qualifications, textbooks, and school-tax reform. In 1904 justice Hugh MacMahon ruled that members of Catholic religious orders who were employed as teachers in Ontario must obtain qualifications commensurate with provincial standards. Archbishops Gauthier, Duhamel, and Denis O’Connor* of Toronto, however, were alarmed that many sisters and brothers might leave their teaching posts rather than attend classes in the “Protestant” atmosphere of the provincial normal schools. Believing that the members of orders were already well qualified, through teachers’ conventions and experience, Gauthier and his colleagues appealed MacMahon’s decision to the Supreme Court of Canada and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, but without success. When John Seath*, Ontario’s superintendent of education, produced legislation early in 1907 that required the proper certification of teaching sisters and brothers, Gauthier opposed the plan, fearing the closure of at least four convents in his diocese and the demise of Catholic schools that employed religious. Declaring the bill “odious and unjust,” he appealed directly to Premier James Pliny Whitney* to allow the teachers to be certified without further qualification. With the passage of the act on 20 April 1907, Gauthier and his colleagues conceded defeat and began working to ensure that the teaching members adapted to the three levels of certification.

Gauthier coordinated efforts by the Ontario bishops to secure better funding for Catholic schools from the government and also to obtain improvements to Copp, Clark’s Canadian Catholic readers series. By 1909 he and his long-time friend Archbishop Fergus Patrick McEvay* of Toronto were the instigators and chief negotiators of a quiet diplomacy to procure for the separate schools a larger share of business and corporation taxes and to have public funding extended to the senior grades of Catholic high schools. At one point in the negotiations, in order to win the desired financial concessions, Gauthier and the bishops were prepared to sacrifice their Copp, Clark Catholic textbooks, which would have been very expensive to revise. Doubts about the wisdom of this course of action arose, however. Gauthier asked Whitney to offer Catholic schools more of the taxes in exchange for which the bishops, after removing the “objectionable features,” would allow public school readers to be used as supplementary texts in Catholic schools. Negotiations continued but in 1910 the bishops’ hopes were dashed when the government shelved plans for Catholic school reforms because of vociferous demands by Franco-Ontarians for the extension of French-language education. Whitney feared that any concessions to the bishops in the midst of these demands would alienate the Orange faction of his government.

The Kingston archbishop’s influence in ecclesiastical politics was complemented by the attention shown him by the apostolic delegate to Canada, Monsignor Donato Sbarretti y Tazza. Their close relationship – Sbarretti sought Gauthier’s advice and assistance on several occasions – was fortunate for the English-speaking bishops as they moved to exert their influence over the church west of the Ottawa River. Gauthier was known to be vehemently opposed to French Canadian clerical nationalists and, as Bishop Thomas Joseph Dowling reported Gauthier’s position to Rome, their “impertinent interference with the affairs of English speaking provinces.” As an integral part of their struggle for control, Gauthier and other English-speaking bishops attempted to secure their own candidate each time a see became vacant. In partnership with McEvay and Archbishop Edward Joseph McCarthy of Halifax, in 1909 Gauthier acquired the services of Father Henry Joseph O’Leary* as the anglophone bishops’ agent at the Vatican. With O’Leary’s aid and Sbarretti’s confidence, Gauthier and his group were successful in several appointments, including that of Michael Francis Fallon* as bishop of London in 1909. Long admired by Gauthier, this controversial cleric was loathed by Franco-Ontarians, particularly in Essex County, for his opposition to bilingual schools.

The “bishop maker” became a victim of his own success. In August 1910 the Vatican named him archbishop of Ottawa, a position left vacant since the death of Duhamel in June 1909. This appointment came in spite of the fact that Gauthier’s name did not appear among the original terna (list of candidates) for Ottawa and that Gauthier himself had recommended the “broadminded” Bishop Joseph-Médard Emard for the difficult task of administering this explosive archdiocese. Out of 266 priests and brothers there, only 30 were not of French origin. Moreover, for much of the decade, French- and English-speaking Catholics in Ottawa had been bitterly divided over who would control the bilingual University of Ottawa and the Ottawa Separate School Board. Infighting among the board’s trustees over teachers’ qualifications and spending had prompted the court case that had led to the provincial law on certification. By 1910 demands for the improvement of bilingual schools, spearheaded by the Congrès d’Éducation des Canadiens Français de l’Ontario [see Napoléon-Antoine Belcourt*], had further polarized the church along linguistic lines in eastern Ontario. In Ottawa, Protestants stood on the sidelines and watched with interest as the various Catholic factions waged war in school-council chambers, in the press, and from the pulpits.

Gauthier’s colleagues knew full well the trouble that faced him. His fellow bishops in Ontario passed a motion of “confidence and good will” as he embarked on the most difficult task of his career. Bishop Paul La Rocque of Sherbrooke, Que., offered his “condolences” in English. In a similar vein, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* expressed his concern about the “overwhelming” burden placed on his good friend, and his regret that some Catholics had been critical of the Vatican’s decision. Francophone Catholics in the archdiocese were distressed by the appointment of Gauthier, whom they considered an anglophone with a French surname. This reaction had been anticipated by Sbarretti, who had received the papal bulls authorizing the appointment in August 1910 but, to avoid too much attention to a controversial selection, withheld the news until after the International Eucharistic Congress in Montreal in September. In speculating about the appointment in Le Devoir on 19 July, Henri Bourassa* had neatly summarized the opinion of French Canadian nationalists when he asserted that Gauthier was “French in name, English in language and education,” of advanced age, and appointed only to secure “the definitive nomination of an English-speaking bishop.” Contrary to Fergus McEvay’s prediction in November that “the crazy opposition” would dissipate, the anger did not subside. When Gauthier was installed at Notre-Dame Basilica on 21 Feb. 1911, both the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste and the Association Canadienne-Française d’Éducation d’Ontario refused to attend.

The bilingual schools question would dog Gauthier for the rest of his life. In 1912, following the Department of Education’s issue of Regulation 17, which prohibited French-language education after the first form, Gauthier was faced with virtual civil war within the Ottawa Separate School Board. Despite his opposition to the francophone demands of 1910, Gauthier took a more moderate position on bilingual schools in the hope that he might reconcile the factions. In 1912 he appealed to Whitney to allow “a larger measure of French to be taught” in bilingual schools attended exclusively by French Canadian children. The premier refused on the grounds that such a measure would create a “third” school system in Ontario.

By 1914 the situation at the school board had deteriorated. French trustees defied Regulation 17 and, as a result, English-speaking trustees sought an injunction to prohibit the francophones from raising debentures for independent schools and paying salaries to unqualified teachers. In June 1915, after an acrimonious election and bitter confrontations between local priests, the board shut its schools. In September they were reopened by order of the Ontario Supreme Court, and the new premier, William Howard Hearst*, appointed a three-person commission to run the board and ensure its adherence to the provincial regulation. English-speaking clergy and laity lined up in support of the commission, while their French-speaking co-religionists condemned it and francophone bishops appealed to Pope Benedict XV to defend French-language education rights. In 1916 the pope responded with an encyclical, Commisso divinitus, which instructed Gauthier’s flock to settle their differences peacefully and not imperil their schools. Neither this intervention nor the mediatory efforts of archbishops Paul Bruchési* of Montreal and Neil McNeil* of Toronto ended the crisis. Later that year, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council upheld Regulation 17 but ruled the Ottawa School Commission illegal, and attempts were made to reconstitute the original board.

During the crisis Gauthier had become increasingly estranged from the francophone Catholics of his diocese. He was notably absent from the biannual congresses of the ACFEO, despite the presence of other bishops, and his francophone priests expressed their disgust at his inability to rein in actions of the English-speaking Catholics. Gauthier tried to maintain a middle course. He instructed his clergy in unequivocal terms to desist from any public discussion of these “vexed questions.” In 1917, in the wake of the papal encyclical and the validation of Regulation 17 by the courts, Gauthier and the Ontario bishops issued a joint pastoral urging Catholics to “obey all the just laws and regulations enacted from time to time by civil authorities” and English-speaking Catholics in particular to consider “sympathetically” the “aspirations and requests” of French Canadian Catholics. The bishops acknowledged the ambiguities of Regulation 17 but endorsed its legality, and echoed the pope by asking that Catholics facilitate “an equitable teaching of the French language together with a thorough acquisition of English.” Despite these pleas, the tension in the Ottawa board continued, and local priests continued to complain about the tactics of “the other side.”

Although weighed down and sometimes demoralized by the schools issue, Gauthier still managed to conduct his day-to-day administrative affairs in efficient fashion, as he had done in Kingston. He continued to monitor the interactions of Catholics and Protestants, noting the increased numbers of mixed marriages, especially in English-speaking parishes. As the Catholic population of his diocese expanded on both sides of the Ottawa River, he approved the construction of church buildings and erected new parishes, including Saint-Bernardin (1912), Ottawa’s Blessed Sacrament (1913) and Saint-Gérard-Majella (1916), Vars (1915), and, in Quebec, Boileau (1915), Fieldville (1915), and Hull’s Saint-Joseph (1913) and Notre-Dame-de-Lorette (1916). He also presided over the creation of the diocese of Mont-Laurier in 1913 out of the eastern section of his territory in Quebec and the reorganization of his suffragan dioceses northwest of Ottawa. In 1915 the vicariate of Timiskaming became the diocese of Haileybury and four years later the prefecture of Northern Ontario was carved out of its northwestern section. In addition, he supported special collections for the erection of a diocesan seminary (a project unrealized in his lifetime) and for home missions to Ukrainian Catholic immigrants.

The pressures of episcopal administration and the linguistic crisis took their toll on Gauthier. After 1918 his health declined and his appearances became less frequent. In 1921 he issued his last significant public statement, a lengthy pastoral on the needs of separate schools in Ontario. As he had earlier in his career, he made an eloquent plea to Catholics to continue the fight for a just share of the tax assessment and for the funding of senior grades in high schools. He had never surrendered his hope that funding equity, as promised in the Separate School Act of 1863 [see Sir Richard William Scott*], could be achieved through concerted effort. He would not witness the attainment of full funding.

Shortly before Christmas 1921 Gauthier was rushed to the Ottawa General Hospital, where he died of uraemia at 2:35 a.m. on 19 Jan. 1922. He was buried in Notre-Dame Basilica. His funeral was attended by Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King*, members of his cabinet, numerous bishops, over 500 clergy and religious, a legion of lay leaders, and his brother and two sisters. In eulogies, former adversaries in the bilingual schools controversy now acknowledged him as a “true friend of the separate schools,” while non-Catholics paid tribute to him as a loyal citizen who had stirred up “the patriotic spirit of his parishioners” during the Great War. Given the challenges of his life and his enormous pastoral contribution, the most fitting tribute came from the Ottawa Citizen, which remarked that he had lived up to his motto, In fide et lenitate. Charles Hugh Gauthier had indeed been strong in faith and gentle in administration.

AO, F 5; RG 80-8-0-863, no.9268. Arch. of the Archdiocese of Kingston, Ont., Gauthier papers. Arch. of the Archdiocese of Ottawa, Blessed Sacrament parish papers; Gauthier papers; Toronto corr. Arch. of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto, ME (McEvay papers); O (O’Connor papers). Archivio Segreto Vaticano (Rome), Delegazione apostolica del Canadà, 157.37; Secretaria di Stato. LAC, RG 31, C1, 1871, Kenyon Township, Ont., div.2: 31. L’Action catholique (Québec), 19 janv. 1922. Canadian Freeman (Kingston), 22 June 1898. Catholic Record (London, Ont.), 2 April, 16 July, 3 Sept. 1898. Catholic Register (Toronto), 26 Oct. 1916, 26 Jan. 1922. Le Devoir, 19 juill. 1910, 22 févr. 1911. Le Droit (Ottawa), 24 janv. 1922. Ottawa Citizen, 19 Jan. 1922. Ottawa Evening Journal, 19 Jan. 1922. La Presse, 24 janv. 1922. La Semaine religieuse de Montréal, 26 janv. 1922. La Semaine religieuse de Québec, 2 févr. 1922. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Canadian R.C. bishops, 1658-1979, comp. André Chapeau et al. (Ottawa, 1980). Robert Choquette, L’Église catholique dans l’Ontario français du dix-neuvième siècle (Ottawa, 1984); La foi: gardienne de la langue en Ontario, 1900-1950 (Montréal, 1987); Language and religion: a history of English-French conflict in Ontario (Ottawa, 1975). L. J. Flynn, Built on a rock: the story of the Roman Catholic Church in Kingston, 1826-1976 (Kingston, 1976). Hector Legros and Sœur Paul-Émile [Louise Guay], Le diocèse d’Ottawa, 1847–1948 (Ottawa, [1949]). M. G. McGowan, The waning of the green: Catholics, the Irish, and identity in Toronto, 1887–1922 (Montreal and Kingston, 1999). Planted by flowing water: the diocese of Ottawa, 1847–1997, ed. Pierre Hurtubise et al. (Ottawa, 1998).

Cite This Article

Mark G. McGowan, “GAUTHIER, CHARLES HUGH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 8, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gauthier_charles_hugh_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gauthier_charles_hugh_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mark G. McGowan |

| Title of Article: | GAUTHIER, CHARLES HUGH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 8, 2025 |