Source: Link

Ditchburn, William Ernest, printer, lacrosse player, political organizer, and office holder; b. 11 Dec. 1862 in Ross (Ross-on-Wye), England, fourth of the eight children of Thomas Lee Ditchburn and Eliza Anne Landells; m. 27 Oct. 1897 Ann Lilian Stainsby Blackett in Victoria, and they had three children, one of whom died young; d. there 11 Nov. 1932.

In 1868, when Billy Ditchburn was a small boy, his family emigrated from England to Ontario. There, he attended public schools in Harwood, Cobourg, and Toronto, communities where his father worked as a photographer, telegrapher, and railway-station agent. In 1875, at age 13, he apprenticed as a printer in Toronto. Five years later he got his first job in the trade at the Ladies’ Journal in that city. When the publisher moved to Mount Forest the next year, Ditchburn followed. There he discovered a love of lacrosse and played for the town’s club. He then moved around Ontario, practising his trade with newspapers in Gananoque (1882–84), Brockville (1884–86), and Ottawa (1887–89), each time joining the local lacrosse team. During this period he established a reputation as a star player.

In 1890 Ditchburn decided to move west, stopping in Winnipeg for the summer, where he helped that city’s lacrosse club win the provincial championship. Later that year he worked for a newspaper in Tacoma, Wash., but, disappointed by the absence of a lacrosse team, he moved to Victoria, where he found employment as a printer with the Victoria Daily Times and later with the Daily Colonist. He joined the city’s lacrosse team and dazzled spectators with his vigour, speed and, as one journalist from the Daily Colonist reported, his “flowing black moustache.” In 1893 he was a member of a Victoria team that toured Ontario and Quebec, losing only one exhibition game.

On 27 Oct. 1897 Ditchburn married Ann Lilian Stainsby Blackett, a Victoria resident whose family had emigrated from England. After the wedding he retired as a lacrosse player, but he soon returned to the sport, acting as a referee until the game declined in popularity following World War I. Early in the 20th century he became part of Victoria’s masonic order.

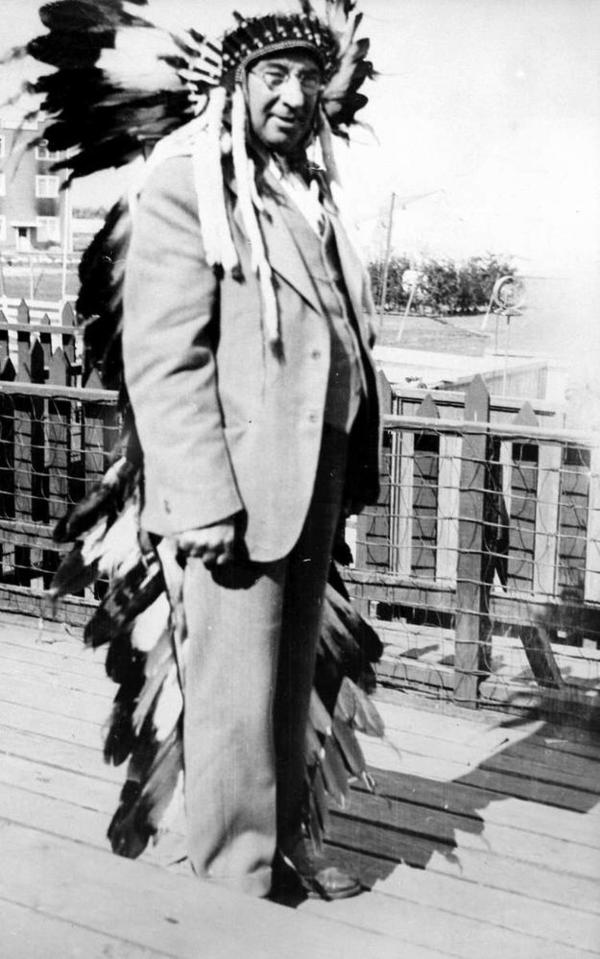

Politically, Ditchburn was active with the city’s Liberals, and in 1908 he was asked to organize the Victoria Liberal Association, which was affiliated with both the federal and provincial parties; the next year, he was elected the association’s president. In 1910 the Department of Indian Affairs abolished the position of superintendent of Indian affairs for British Columbia and divided the province into three administrative districts. As an active member of Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s governing federal party, Ditchburn was well positioned for a patronage appointment, and was promptly named inspector of Indian agencies for the Southwestern Inspectorate, which had its headquarters in Victoria. At this time he gave up printing. In 1917 he would be promoted to chief inspector for the province, and, in 1923, appointed commissioner of Indian affairs for British Columbia, a role he would fill until his retirement.

His first position made Ditchburn responsible for the Cowichan, Kwahkewlth, Lytton, New Westminster, and West Coast agencies. He was thus charged with conducting tours of inspection and delivering reports to Ottawa on the condition of indigenous communities concerning such matters as health, economic activity, moral conduct (which included liquor use and marriage customs), and education. The quality of houses was of particular interest to him; it was his preferred measure of progress towards what he considered to be civilization. For example, he deplored the fact that in the Kwahkewlth agency many fine canoes were being built but little was being done to improve housing. Conversely, the Songhees, who, under his supervision, moved from a reserve near Victoria to one at Esquimalt Harbour in 1911, took the opportunity to build good houses in their new location. Ditchburn commented on their efforts in his annual report for 1914–15: “A stranger passing by this reserve would not for a moment imagine that the property belonged to Indians.”

Over the years Ditchburn criticized poor attendance at day schools on reserves. He blamed the situation on seasonal migrations related to fishing and harvesting and the tendency to hold potlatches during the winter months. His proposed solution was to expand accommodation in industrial and boarding schools, a strategy adopted by the department after World War I. But as the number of residential institutions grew, he became increasingly aware of their shortcomings [see Peter Henderson Bryce]. In 1920 he would write a report in which he attributed declining student health to poor food, excessive labour, and too many religious exercises in Roman Catholic schools.

Ditchburn considered the potlatch a “deplorable custom” that disrupted school attendance, wasted time and money, and brought together large crowds in unsanitary conditions. In 1913, after a visit to Alert Bay, where the ceremony was often held, he wrote to department headquarters urging that section 149 of the Indian Act, which outlawed the potlatch [see Israel Wood Powell*], be enforced. The new deputy superintendent of Indian affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott*, agreed, and prosecutions immediately followed. This repression discouraged the potlatch for a time but failed to eliminate it. Many indigenous people openly defied the law, particularly the Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka’wakw). Leaders Johnny Bagwany, who offered himself as a “martyr” for the cause, and Ned Harris were tried and found guilty in 1914 but received suspended sentences. Others became adept at evading the law and protested that section 149 should be repealed. A number of anthropologists (including Franz Boas* and Charles Frederic Newcombe*) and politicians (such as Conservative mp Herbert Sylvester Clements) publicly supported indigenous claims for the right to conduct potlatches, but Ditchburn, with the full backing of the department, refused to compromise. In 1931 he wrote that the department’s unambiguous aim was “to eradicate this practice entirely as there appears to be no half-way measures that could be put into effect.”

In 1912 Ditchburn had learned that the owners of sealing vessels were entitled to compensation under the Fur Seal Treaty of 1911, which banned seal hunting in the northern Pacific. Since this treaty deprived many indigenous people of lucrative seasonal employment, he began to press department headquarters to ensure that they also received compensation. Mainly because of his initiative, arrangements were made for indigenous sealers to prepare and submit their claims. Some department officials worried that the legal and travel costs of distributing compensation funds would be greater than the compensation itself, and Ditchburn had to overcome their concerns. After much deliberation, he was given $13,295.25 in 1916 to be divided among 902 indigenous sealers, out of a total of $200,000 received by Canada in compensation from the United States.

Between 1913 and 1916 a royal commission, which came to be known as the McKenna–McBride commission [see James Andrew Joseph McKenna*], had examined the state of reserves in British Columbia and recommended some modifications to their boundaries. The commission was supposed to resolve a long-standing dispute between Ottawa and Victoria over indigenous lands. The federal government wanted to endorse the commission’s recommendations, and Ditchburn’s job was to persuade the reluctant provincial government to do so as well. Victoria considered the recommendations too generous to indigenous people and the matter was stalled until 1920, when a review of the commission’s work was accepted. The review was conducted by Ditchburn, who represented Ottawa, J. W. Clark, who acted for the province, and James Alexander Teit*, a British Columbia ethnographer and political activist who represented indigenous interests. During what came to be known as the Ditchburn inquiry, bands made several requests for additional lands, most of which Ditchburn rejected, but those he considered reasonable were turned down by Clark. Indeed, Ditchburn found Clark to be inflexible and parsimonious, and the final report mainly proposed further reductions to reserves. Victoria and Ottawa endorsed the report of the royal commission as amended by Ditchburn and Clark in 1923 and 1924 respectively. The federal–provincial agreement was unacceptable to many indigenous people. Since the establishment of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia in 1909, they had maintained a persistent agitation – notably through the work of indigenous leaders Peter Reginald Kelly* and Andrew Paull – in the hope that both levels of government would recognize their land claims, a goal that was never achieved.

Deputy Superintendent Scott had full confidence in Ditchburn, knowing that he could be relied on to vigorously apply departmental policy. Ditchburn repaid this confidence with tireless devotion to his job, refusing to take the vacations to which he was entitled. By the 1930s, however, his health was in decline, and in June 1932 he retired from service. He died on 11 November at his home on Linden Avenue in Victoria, and was interred at Ross Bay Cemetery after a funeral service conducted by the masonic order.

William Ernest Ditchburn played a significant role in managing the Department of Indian Affairs in British Columbia for nearly two decades. Although he demonstrated occasional understanding of indigenous rights and needs, for the most part he diligently implemented a policy that was repressive in conception and application.

B.C., Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations (Victoria), file 026076, sect.3. LAC, RG10, vol.3629, file no.6244-2. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 1897–1932. Victoria Daily Times, 1911–32. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1912, 1914, 1916 (reports of the Dept. of Indian Affairs, 1911, 1913, 1915). Douglas Cole and Ira Chaikin, An iron hand upon the people: the law against the potlatch on the northwest coast (Vancouver, 1990). J. S. Milloy, A national crime: the Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879 to 1986 (Winnipeg, 1999). D. G. Paterson, “The North Pacific seal hunt, 1886–1910: rights and regulations,” in British Columbia: historical readings, ed. W. P. Ward and R. A. J. McDonald (Vancouver, 1981), 343–66. E. O. S. Scholefield and F. W. Howay, British Columbia from the earliest times to the present (4v., Vancouver, 1914). E. B. Titley, A narrow vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver, 1986).

Cite This Article

E. Brian Titley, “DITCHBURN, WILLIAM ERNEST,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 8, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ditchburn_william_ernest_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ditchburn_william_ernest_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | E. Brian Titley |

| Title of Article: | DITCHBURN, WILLIAM ERNEST |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | January 8, 2025 |