![Photograph of Frank Darling

Date(s): [192-?] (Creation)

Repository: Dalhousie University Archives

Reference code: MS-2-718, PB Box 14, Folder 19

Peter B. Waite fonds Original title: Photograph of Frank Darling

Date(s): [192-?] (Creation)

Repository: Dalhousie University Archives

Reference code: MS-2-718, PB Box 14, Folder 19

Peter B. Waite fonds](/bioimages/w600.14051.jpg)

Source: Link

DARLING, FRANK, architect; b. 17 Feb. 1850 in Scarborough Township, Upper Canada, son of William Stewart Darling, a Church of England clergyman, and Jane Parsons; d. unmarried 19 May 1923 in Toronto.

The eldest son of the rector of Scarborough and later of the Church of the Holy Trinity in Toronto, Frank Darling was educated at Upper Canada College in Toronto and Trinity College School in Weston (Toronto). In 1866, after a short time as a bank teller, he joined the architectural office of Thomas Gundry and Henry Langley* as an apprentice. In late 1869 or early 1870 he left Toronto to train in London with one of the greatest architects of the age, George Edmund Street. Before returning in 1873, he also worked briefly with Arthur William Blomfield. This British experience had a profound effect on Darling. From Street he learned that the principles of Gothic architecture could form the basis of modern design. From Street’s students Richard Norman Shaw, William Eden Nesfield, and Philip Speakman Webb he saw how historical forms could be skilfully adapted to meet the needs of contemporary life.

Darling began private practice in Toronto in 1873, when he entered into partnership with Henry Macdougall. His first commissions came from the city’s Anglicans, and included the churches of St Matthias (1873-74), St Thomas (1874), and St Luke (1881) as well as the convocation hall (1877) and chapel (1884) of Trinity College. This early work was mostly executed in brick in a manner reminiscent of Street, Shaw, and Nesfield. Other projects show Darling in a continuing state of artistic experimentation: the Home for Incurables (1879-81) is an exercise in Shaw’s eclecticism and the Victoria Hospital for Sick Children (1889) reveals the influence of American Henry Hobson Richardson.

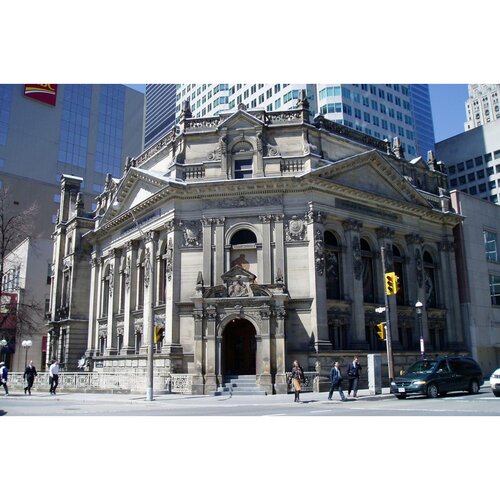

In 1880 Darling, who was then in partnership with Samuel George Curry (a Port Hope native), had submitted a design modelled on Street’s plan for the Law Courts in London to the competition for Ontario’s new parliament buildings. Although Darling placed first, delays and back-room deals meant that his plan would never be built [see Kivas Tully*]. The competition nonetheless brought him recognition and, in 1885, the chance to do something new: a branch in Toronto for the Bank of Montreal. Its obtusely angled site at the corner of Front and Yonge was difficult, but he responded with a masterful essay in the newly fashionable classical mode, in which a carefully ornamented stone façade introduced a stunning glass-domed hall [see Joseph McCausland*]. Functional and stylish, the bank was a success for Darling. In it he anticipated the taste for monumental public architecture that would sweep North America in the first decades of the 20th century.

After 1885, Darling’s commissions, besides the hospital, included the Toronto Club (1888) and additions to Trinity College. In 1892 he took into partnership an associate from the hospital project, the British-trained John Andrew Pearson*, who would work with him for the rest of his career. The years of Darling’s greatest achievement began in 1898, when he was retained by the Canadian Bank of Commerce to design branches in Winnipeg and Toronto. Like its competitors, the Commerce found architecture an effective vehicle for self-promotion. Darling subsequently designed dozens of branches for the Commerce, as well as for the Metropolitan, Sterling, Dominion, Union, and Nova Scotia banks. Most of the Commerce buildings featured façades of stone and brick and were grandly classical in the manner of the English baroque or the French École des Beaux-Arts. They ranged from impressive structures with giant columns and massive stone entablatures, as in Montreal (1903-8), Vancouver (1906-8), and Winnipeg (1910-12), to handsome pavilions scaled to the needs of small towns and city neighbourhoods. Particularly charming were a series of prefabricated frame branches in frontier towns across the west that had been produced, shipped, and erected by the British Columbia Mills, Timber and Trading Company [see John Hendry*]. Darling’s work for the Commerce brought social and financial success and offers of patronage, especially from a small circle of powerful Toronto businessmen. Besides George Albertus Cox* and Byron Edmund Walker, both presidents of the Commerce, this group included a childhood friend, Dominion president Edmund Boyd Osler, as well as meat packer Joseph Wesley Flavelle*, for whom he designed a house at Queen’s Park (1901-2). Among his other important projects from this period were Convocation Hall at the University of Toronto (1904-7), the Royal Ontario Museum (1909-14), the Toronto General Hospital (1909-13), the Winnipeg Grain and Produce Exchange (1909-10), new buildings for Dalhousie University in Halifax (1912-15), and the headquarters of Sun Life Assurance in Montreal (1916-18).

The scale of this production had an enormous impact on the look of Canada’s towns and cities. At a time when many businessmen preferred to hire American architects for high-profile commissions, Darling’s bank architecture became recognizable for its balance of English and North American trends. For many buildings he modulated his characteristically classical language to suit specific conditions, as in his frequent use of Romanesque motifs on the campus of the University of Toronto. His accomplished, thoughtful approach to design, artistic confidence, and high standard of execution won him the admiration of his peers. He was made a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1886, president of the Ontario Association of Architects in 1895, and a director of the Toronto Guild of Civic Art in 1907. Darling claimed to abhor professional infighting, but, as president of the OAA, he became enmeshed in the association’s unsuccessful efforts to secure compulsory registration, a step not all architects supported. He nevertheless remained a popular figure, known increasingly for his bold projects. Named to the federal planning commission for Ottawa and Hull in 1913, he was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects two years later (the only Canadian architect so recognized) and honorary doctorates from the University of Toronto (1916) and Dalhousie (1922). Darling’s professionalism generated equal respect among his clients. In his ongoing work for Dalhousie, which included Shirreff Hall (1920-21) [see Jennie Grahl Hunter Shirreff], Darling, in the estimate of university historian P. B. Waite, was “ingenious, flexible, sensitive to local conditions, and best of all, willing to listen to suggestions.” A close friend, architect C. Barry Cleveland, maintained that he stood “for absolutely straight and upright dealing.”

Darling combined a quiet charm with refined tastes. According to one biographer, “He had a good-natured tolerance, and on occasion he was master of the mordant phrase. A poor story-teller, but a good listener, geniality and wit went hand in hand with him, more especially when he could be provoked into exercising his ability as an architectural critic.” His collection of etchings and prints was strong in 17th-century French portraiture; his architectural library represented 20th-century modernists and landscapists as well as earlier revivalists. He was an enthusiastic golfer and clubman, and a conservative in politics. A lifelong bachelor, he was decidedly loyal to his family and friends; his widowed mother lived with him for several years before her death in 1909, and he took a particular interest in his nieces and nephews. In his will, Darling, who deeply regretted his inability to speak French and German, left a sum for a great-nephew’s education, especially in the “modern languages.” Valued at more than $183,000, his estate would be distributed largely among his relatives, his servants and chauffeur, and J. A. Pearson. Provision was also made for the continued residential and financial needs of an old Scarborough acquaintance and her separated daughter. After eight months of poor health due to heart trouble, Darling died in May 1923 at his home at 11 Walmer Road. He was buried in the family plot at St John’s, Norway (Toronto).

Darling had avoided controversy and written little. Others championed his architecture. Critic and professor Percy Erskine Nobbs* saw in his work support for his own belief that Canadian architecture could develop a distinctive voice only by charting a middle ground between the architectural cultures of Britain and the United States, with careful attention to local needs. This approach had been Darling’s modus operandi. At a time of rapid architectural change, his ability to combine ideas, materials, and techniques from London, New York, and Chicago into a unified whole (without copying) was exceptional. Buildings such as his Bank of Nova Scotia in Winnipeg (1907-8) display a hybrid quality that was expressive of the complex patterns of Canadian intellectual and cultural life in the years leading up to World War I. The new houses of parliament in Ottawa (1916-27), designed by Pearson and Jean-Omer Marchand*, reflect in their spirit of progressive traditionalism, blend of references, and balance of old and new the substantial impact of Darling and his office. By adapting the fashions of the day to the wishes of his clients, he had helped shape an independent voice for Canadian architecture and lay the foundation for the creative exploration of Canadian themes by such architects as John MacIntosh Lyle* in the 1920s.

Frank Darling’s address as president of the Ontario Assoc. of Architects appears in Canadian Architect and Builder (Toronto), 9 (1896), no.2: 17-19.

AO, RG 22-305, no.47775; RG 80-8-0-910, no.4200. LAC, RG 31, C1, 1901, Toronto, Ward 4, div.2: 7 (mfm. at AO). Univ. of Waterloo Library, Doris Lewis Rare Book Room (Waterloo, Ont.), William Dendy, “Frank Darling, 1880-1923, Canadian architect” (typescript with plates, 1979). Globe, 21-22 May 1923. E. [R.] Arthur, Toronto, no mean city ([Toronto], 1964; 3rd ed., rev. S. A. Otto, 1986). James Borcoman et al., Money matters: a critical look at bank architecture (exhibition catalogue, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, 1990). Canadian annual rev., 1913: 333; 1916: 797; 1921: 241. Kelly Crossman, Architecture in transition: from art to practice, 1885-1906 (Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1987). William Dendy, Lost Toronto (Toronto, 1978). William Dendy et al., Toronto observed: its architecture, patrons, and history (Toronto, 1986). M. E. and Merilyn McKelvey, Toronto, carved in stone (Toronto, 1984). G. E. Mills and D. W. Holdsworth, “The B.C. Mills prefabricated system: the emergence of ready-made buildings in western Canada,” Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and Hist. (Ottawa), no.14 (1975): 127-69. National Gallery of Canada, Canadian art, ed. C. C. Hill et al. (2v., Ottawa, 1988-94), 1: 254. Geoffrey Simmins, Ontario Association of Architects: a centennial history, 1889-1989 (Toronto, 1989). David Spector, “The buildings of the Winnipeg-based Union and Northern Crown banks: a glimpse into early twentieth century corporate architecture,” Manitoba Hist. (Winnipeg), no.21 (spring 1991): 25-31. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). Toronto Region Architectural Conservancy, Terra cotta - artful deceivers (Toronto, 1990). P. B. Waite, The lives of Dalhousie University (2v., Montreal and Kingston, 1994-98), 1.

Cite This Article

Kelly Crossman, “DARLING, FRANK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/darling_frank_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/darling_frank_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kelly Crossman |

| Title of Article: | DARLING, FRANK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |