Source: Link

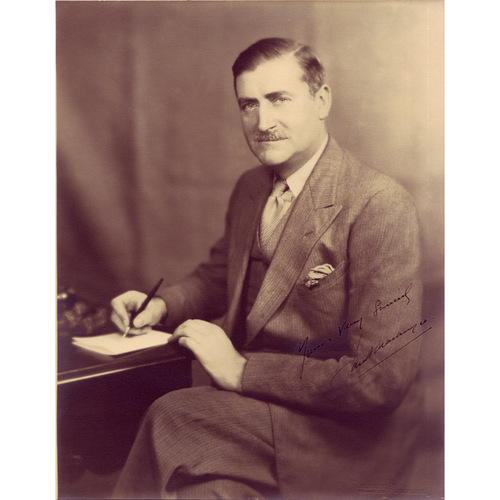

MACKENZIE (McKenzie), IAN ALISTAIR (named at birth John Alexander), translator, author, lawyer, militia officer, army officer, and politician; b. 27 July 1890 in Culkein Stoer, Sutherland, Scotland, son of George Mckenzie and Anne MacRae; m. 10 Sept. 1947 Helen Mary MacRae in Ottawa; they had no children; d. 2 Sept. 1949 in Banff, Alta.

Ian Alistair Mackenzie was a descendant of Highland crofter folk and made much of that fact throughout his life. His father fished and raised livestock in the remote northwest parish of Assynt. The family spoke Gaelic, and Ian, his parents, and his 11 siblings, 10 of whom reached adulthood, subsisted mainly on porridge, herring, and potatoes, with meat served only on Sundays after church. Mackenzie remembered well stories of the harsh eviction of one of his grandmothers. As he recounted, he was brought up on “teetotalism, Presbyterianism and Liberalism.” A predilection for alcohol, however, would eventually blight his career, but the influences of religion and radicalism remained strong.

Benefiting from the rigorous Scottish school system, he attended high school in Kingussie, Inverness-shire, on a scholarship. He then went to the University of Edinburgh, graduating in 1911 with an ma in classics. That year he campaigned for the National Insurance Act, advanced by David Lloyd George, the chancellor of the exchequer in the Liberal government of Herbert Henry Asquith. Subsequently passed, this major social-reform legislation introduced medical and unemployment benefits. As Mackenzie would recall, the experience confirmed his belief in the need for “a strong, militant Liberal Party.” Thanks to a research scholarship, he enrolled in the School of Irish Learning in Dublin. There he translated Gaelic documents, wrote papers on a variety of Celtic topics, and assisted the Reverend Donald Maclean in the preparation of The spiritual songs of Dugald Buchanan (Edinburgh, 1913). Mackenzie developed what would be a lifelong interest in poetry and was something of an amateur versifier. He next studied law at the University of Edinburgh; at some stage of his academic career, he also joined the University Officers’ Training Corps. In 1914 he received his llb. He could not, however, afford the fees for admittance to the Scottish bar and emigrated to Vancouver that year. Mackenzie moved easily in his adopted city, where he articled at the firm of Bodwell, Lawson and Lane. In Canada he was known as Ian Alistair, a makeover that emphasized his Scottish ancestry.

When war was declared in August 1914, Canada took up arms in Europe as a constituent part of the British empire. The following July the Vancouver-based 72nd Regiment (Seaforth Highlanders of Canada) was authorized by the minister of militia and defence, Samuel Hughes*, as the 72nd Battalion (Seaforth Highlanders of Canada). Its commander was John Arthur Clark*. Mackenzie was commissioned lieutenant in the unit on 28 Dec. 1915. He was an imposing figure who stood 6 feet 2¾ inches tall, weighed 174 pounds, and had a scar on his forehead. In the words of journalist Austin Fletcher Cross, Mackenzie spoke with “the breath of heather in his voice.” He embarked for England on 19 May 1916 and qualified in a grenade course before proceeding to France that August. On 26 December he was posted to the Canadian training depot in Shorncliffe, England, for duty with the Canadian Railway Troops (CRT), a formation led by Brigadier-General John William Stewart*, another Sutherland Scot who had settled in Vancouver. Mackenzie was taken on strength by the CRT base depot on 16 Jan. 1917. He returned to France on 22 March with the 3rd Battalion of the CRT. In July he was attached to the CRT headquarters, a post he held for five months. During this time he helped keep the unit’s war diary. He reported hearing “heavy fire” but never noted coming under attack himself, though he likely had seen action while serving in the 72nd Battalion. He was made a temporary captain on 29 March 1918. In November he was sent to England on special duty, and the next year he was mentioned in dispatches. Mackenzie sailed back to Canada in February 1919 and was discharged on 25 March with “no disability due to or aggravated by service.” His personal diary suggests that, all in all, he had a good war.

Less than a month after arriving home, Mackenzie was called to the British Columbia bar and set up a practice with James Bruce Boyd; in 1922 Douglas Armour joined them and they operated as Armour, Mackenzie and Boyd until 1924. Soon after his return, Mackenzie became active in the Great War Veterans’ Association of Canada (GWVA), an assertive ex-service organization that had been formed in Winnipeg in 1917. He called for an increase in the gratuity paid to those who had served and for “equality of sacrifice” between “the nation’s manhood and the nation’s wealth” – a message that tapped into seething public anger about wartime profiteering. Urging unity among veterans, he cautioned against the kind of class conflict that was evident during the Winnipeg General Strike [see Mike Sokolowiski*] and the Vancouver sympathy strike in 1919. As a soldier advocate representing the British Columbia mainland, he helped several veterans make pension claims. In January 1920 he was elected president of the GWVA’s Vancouver branch and was serving on the provincial executive. The following year he joined the organization’s dominion executive and promoted unity among veterans’ organizations, a cause that would lead to the formation, in 1925, of the Canadian Legion of the British Empire Service League.

Around this time Mackenzie also became an important speaker for the Moderation League, which, under the chairmanship of Henry Ogle Bell-Irving*, sought to end Prohibition. In a plebiscite held on 20 Oct. 1920, British Columbians voted 92,095 to 55,448 to initiate the sale of bottled spirits and beer under government control. Liberal premier John Oliver*, a Prohibitionist, called a general election for 1 December, with liquor-control policy as a central issue. Attorney General John Wallace de Beque Farris recruited Mackenzie to run. The Liberals won 25 of 47 seats. Mackenzie was elected an mla, having placed second among the six members elected for the riding of Vancouver City. In his new position he continued to speak on behalf of veterans, arguing that a proposed independent liquor commission should include at least one returned soldier, government liquor stores should hire disabled veterans, and hotels and private clubs such as those operated by veterans should be allowed to sell beer by the glass.

Mackenzie supported other social-reform measures, including the introduction of a 48-hour workweek and an 8-hour workday. He urged the construction of a proper campus for the University of British Columbia, dramatically piling on his desk in the legislature a student-organized petition with 50,000 signatures. As president of the Vancouver branch of the GWVA, he had sought the enfranchisement of Japanese Canadian veterans of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), which would be granted in 1931. He had no qualms, however, about voicing his strong views on Asiatic exclusion in other respects. As an mla he won unanimous approval for a motion to amend the British North America Act to permit the province to deny Asians the right to acquire property or engage in provincial industries. “Economically,” he asserted, “we cannot compete with them; racially we cannot assimilate them; hence we must exclude them from our midst, and prohibit them from owning land” (Daily Colonist, 22 Nov. 1922). For Mackenzie, this conviction became an idée fixe. Re-elected in 1924, he urged Ottawa to halt Japanese immigration in order “to guarantee a white red-blooded Canada” (Vancouver Daily Province, 12 June 1924). He also campaigned for lower freight rates for the province. As a second-term mla he supported the province’s adoption, in 1927, of Ottawa’s old-age pension scheme, which he hoped would be the precursor of insurance schemes to cover maternity leave, invalidism, accidents, and unemployment.

Following Oliver’s death, John Duncan MacLean became premier on 20 Aug. 1927. Mackenzie was made provincial secretary on 5 June 1928, one day before a general election was called. On 18 July the Conservatives swept to power under the leadership of Simon Fraser Tolmie*, but Mackenzie was re-elected, this time for North Vancouver. He was a feisty opposition member, attacking the new government for its fiscal policies, charging it with dismissing veterans from civil-service posts, and calling for the completion of the Pacific Great Eastern Railway [see Sir Richard McBride*] to the Peace River, an issue that he would later pursue as a member of parliament. When in 1930 he accused public-accounts committee chairman Harold Despard Twigg of acting like Fascist leader Benito Mussolini, Twigg challenged him to step outside. Mackenzie accepted, but others intervened before the men came to blows.

After the legislative session ended Mackenzie went to Scotland to visit his mother, who had been widowed the year before. En route home he stopped in Ottawa, where he dined with Liberal prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King. The two had much in common: both believed in maintaining unity within the British empire but also in increasing Canada’s autonomy in imperial relations. On 30 May 1930 Governor General Lord Willingdon [Freeman-Thomas], acting at King’s request, dissolved parliament and called an election. The prime minister needed to replace James Horace King*, recently appointed to the Senate, as the British Columbia representative in his cabinet. He chose the “alert & active” Mackenzie, as he described him in his diary, thinking he would make a “good run” in Vancouver Centre. On 27 June Mackenzie became minister of immigration and colonization and superintendent general of Indian affairs, and resigned from the provincial legislature.

Mackenzie conducted a spirited campaign in the weeks leading up to the 26 July federal election. Venturing into the Calgary riding of Conservative Party leader Richard Bedford Bennett, he vigorously defended the government’s economic and trade policy before an audience of 3,000. At home, where he was battling incumbent Henry Herbert Stevens*, he reiterated that he stood for “white labor” (Province, 26 July 1930) and promised the dismissal of Chinese cooks employed on the Canadian National Railways ship Prince Henry. At the polls, he defeated Stevens by a vote of 12,064 to 10,023. Nationally, however, the Conservatives won a majority under Bennett, thus cutting short Mackenzie’s budding cabinet career. As a rookie mp, Mackenzie cultivated King, now leader of the opposition, addressing him as “Chief.” He made the rounds for the national Liberal Party, spoke up for British Columbia’s interests, burnished his credentials as a left-leaning reformer, and became known as a skilful parliamentary debater. He also started to acquire a reputation for drinking, and in the caucus he found a boon companion in Quebecer Charles Gavan (Chubby) Power*, another Great War veteran who liked to raise a glass. As well, Mackenzie established a friendship with the effervescent Mitchell Frederick Hepburn*, who would become the Liberal premier of Ontario in 1934.

Bennett had come to power with the promise of remedying the economic downturn that would metastasize into the Great Depression. During the special September 1930 parliamentary session, Mackenzie attacked the prime minister’s proposed tariff hikes as a “gigantic fiscal experiment” and claimed that new customs legislation might mean Soviet-style control in Canada. On 27 March 1931, in his first full parliamentary speech, Mackenzie admitted that the mounting financial crisis had international causes. Yet he accused the government of failing “absolutely and completely not only to end unemployment, but even to remedy it.” In January 1932 he attacked Bennett for adopting a policy of “suicidal economic nationalism.” After a visit to the United Kingdom he dropped in on the Imperial Economic Conference being held in Ottawa that summer; he was not impressed. On 26 September Vancouver papers quoted him as saying that the trade agreements negotiated at the Ottawa meetings were “a leap in the dark.” In an address to Vancouver’s Laurier Club that day, he urged the creation of a central bank to separate “financial policy from the private business of money lending” and advised the Liberals to adopt a “progressive and constructive radical outlook.” Speaking in the House of Commons a month later, he detailed 14 objections to the Ottawa agreements, and charged the Bennett government with looking “exclusively to the interests of the coupon clippers” while ignoring the urgent need for monetary and currency reform. Subsequently, Mackenzie called for the establishment of a national committee to review the financial system. Unemployment, he maintained, was a federal problem, and Ottawa was on the wrong track in attempting to address it through provincial and municipal governments. The following May he attended the World Monetary and Economic Conference in London while he was in Britain to see his mother, whose health was failing. He disparaged Bennett’s performance during the proceedings but welcomed the prime minister’s recruitment of Lord Macmillan to chair a royal commission on banking and currency in Canada. Back home he delivered national radio addresses in which he asserted that monopolies must be given their “marching orders,” and he made the case for a “free collectivism,” whereby the state would act to prevent “cycles of boom and depression.” What was needed, in his opinion, was “capitalism tempered by democratic control.”

In British Columbia Mackenzie had a kindred spirit in Thomas Dufferin Pattullo*, the left-leaning leader of the provincial Liberal Party. After Tolmie called an election for 2 Nov. 1933, Mackenzie toured the province. In a speech at Revelstoke on 3 October he called the hapless Conservative administration “the most incompetent government” in provincial history, and he accused the newly formed Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), headed by James Shaver Woodsworth, of having no provincial leader and a platform that was “80 per cent revamped liberalism and 20 per cent socialistic dynamite.” Pattullo, who used the slogan “Work and wages,” swept to power in Victoria. After the election, however, Mackenzie advised the new premier to give priority to getting the government’s finances in order.

By the mid 1930s Mackenzie was a leading figure in the national Liberal Party. In April 1935, speaking at a rally in Montreal, he promised a platform based on “national reconstruction” (Province, 6 April), to be facilitated by a dominion–provincial conference that would consider necessary amendments to the British North America Act. He also urged that the recently established Bank of Canada, created on the recommendation of the Macmillan royal commission, be put under public rather than private ownership. That change would happen soon. These plans were the Liberal answer to the constitutional obstacles faced by the Rooseveltian New Deal that Bennett had offered in January, much of which would be struck down by the courts. When the embattled Bennett finally called an election for 14 October, Mackenzie had a tough fight in Vancouver Centre, with the CCF very much a threat. Although he favoured parts of the CCF platform, he argued that “socializing industry and finance” would “result in havoc” (Province, 2 October). He called CCF supporters “advanced Liberals” who had “gone astray” (Province, 9 October). At the polls he barely squeaked through, earning 7,658 votes compared with 7,522 for his CCF challenger. King, who had led the Liberals to a big victory under the slogan “It’s King or chaos,” named Mackenzie minister of national defence as of 23 October. Vancouver Sun reporter Charles Norman Senior followed him to Ottawa as his capable amanuensis. Less than two years later journalist Cecil Scott observed that Mackenzie’s waistline was “becoming more evident” and “his chin … dividing horizontally” but he still looked “fine in kilts” and was an enthusiastic dancer of “the Highland fling” (Province, 9 Jan. 1937)

After years of budget cutbacks, the Department of National Defence was, as Mackenzie reported to the prime minister, in an “astonishing and atrocious condition,” a view shared by senior military officials such as Henry Duncan Graham Crerar*. Mackenzie secured appropriations, made administrative changes, and launched expert studies. In keeping with government policy on imperial relations, he emphasized home defence: if, as he said in the house, “Canadian boys” had to defend their country, they should be “armed and equipped with the most modern and efficient machinery” the dominion could provide. On 26 July 1936 he represented the government at the unveiling by King Edward VIII of the Vimy Ridge memorial, designed by Walter Seymour Allward* to honour the Canadians who had fallen in the Great War. About 6,500 Canadian veterans were on hand for what Mackenzie called in his address a “pilgrimage of peace.” Later that year Mackenzie rebuked Viscount Elibank, the president of the Federation of Chambers of Commerce of the British Empire, for questioning the adequacy of Canadian defence policy. Privately, he took the governor general, Lord Tweedsmuir [Buchan*], to task for similar public comments.

In the spring of 1937 Mackenzie blundered during the strike by workers at General Motors of Canada Limited in Oshawa, Ont. His pal Mitch Hepburn, now Ontario’s premier, believed that the strike, led by the Committee for Industrial Organization, was communist inspired, and in his determination to stop it he asked Ottawa for reinforcements from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. King was opposed to Hepburn’s request. By coincidence, on 14 April, while the cabinet was considering the issue, Mackenzie was in Toronto having a three-hour lunch with Hepburn and Globe and Mail owner Clement George McCullagh*. A front-page editorial in the paper’s next edition announced that the federal government was behind Hepburn “100 per cent,” the message having been “brought from Ottawa by Hon. Ian Mackenzie, Minister of Defense.” Hepburn was quoted as saying that the minister had promised everything that was required. An embarrassed Mackenzie immediately wired King to insist that he “would not dream of even suggesting government policy.” “Personal friendship construed deliberately into government attitude” was his explanation. King ordered the embattled minister to issue an immediate denial. Hepburn, unwilling to back down even for a friend whose judgement had probably been clouded by alcohol, insisted that Mackenzie had uttered the words as reported.

Mackenzie was among the Canadians present at the coronation of King George VI on 12 May 1937. Afterwards he attended the Imperial Conference in London. In the event of a war involving Great Britain, the prime minister wanted to avoid commitments that would limit Canadian autonomy or split the country. Loyal to this view, Mackenzie advised his deputy minister during preparations for the conference that the most valuable assistance Canada could offer was information about its resources of raw material and food and its ability to provide supplies, equipment, and ammunition. In the 1938 estimates he stressed that any Canadian military action would result from the nation’s own decision, not from any commitment to the British empire.

During the 1938 session Mackenzie’s anti-Asian rhetoric was tested. Anti-Japanese sentiment had been rising in British Columbia, and Alan Webster Neill*, the independent mp for Comox-Alberni, introduced three different bills to ban Japanese immigration. After the first, Mackenzie wrote to the prime minister, proposing to head off Neill by stating that the government would negotiate immigration issues with Japan, investigate “the entire Oriental problem in British Columbia,” and deport illegal immigrants. King, however, authorized him only to announce an intensive investigation of illegal immigration and the subsequent deportation of any offenders who were found. Neither this statement nor Mackenzie’s declaration that the government’s greatest responsibility was to preserve peace and maintain good relations with Japan assuaged Neill. A procedural action killed Neill’s second bill and saved Mackenzie from having to absent himself; given his own views, he could not oppose the measure, but neither could he break cabinet solidarity. During the 24 May debate on Neill’s third bill, which included a requirement that immigrants pass a language test, Mackenzie argued that an “oriental nation” could simply teach English or French to intending emigrants and thereby easily send “thousands and thousands” of Asians to British Columbia. Exclusion alone, he maintained, would not resolve problems arising from Asian immigration, and he accepted King’s argument that legislation denying Japanese entry would greatly embarrass Great Britain. Other tactics were needed. As minister he concentrated defence expenditures on the Pacific coast for what he called “strategical reasons.”

Beginning in September 1938, Mackenzie became embroiled in the biggest controversy of his career, one that would irrevocably damage his reputation and eventually cost him his position as head of national defence. Two years earlier he had received an unofficial enquiry about the possibility of the British government manufacturing munitions in Canada. This suggestion led to his facilitating an arrangement whereby the John Inglis Company of Toronto was to produce 7,000 Bren machine guns for Canada and 5,000 for the United Kingdom. Mackenzie boasted that the deal would bring in $2 million. William Arthur Irwin*, the associate editor of Toronto-based Maclean’s magazine, obtained a copy of the contract. Having noticed discrepancies between what it contained and what Mackenzie had stated in the House of Commons, Irwin commissioned journalist and distinguished war veteran George Alexander Drew*, who would soon become leader of Ontario’s Conservative Party, to write an investigative article. Called “Canada’s armament mystery!,” it caused an uproar when it appeared in the 1 September issue. In the Financial Post (Toronto), which was also owned by John Bayne Maclean’s publishing company, Drew had earlier attacked the government, and specifically Mackenzie, for not providing the armed forces with necessary equipment. He now questioned the terms of the cost-plus contract, which had been made without tenders. While he did not charge specific individuals with wrongdoing, Drew did imply that some had enjoyed unusual profits, and he fingered Mackenzie as the mastermind of the whole shabby arrangement. In response the government appointed Henry Hague Davis of the Supreme Court of Canada as a one-man royal commission to inquire into the contract. Mackenzie did not acquit himself well during his testimony: he seemed unaware of the details about what had happened and was obviously wholly dependent on his staff. Even his friend Chubby Power would later write that Mackenzie viewed his role in the department as that of a figurehead; while his attendance in the house had always been commendable, he spent little time in his office.

In his report Davis blamed no individual but criticized the defence department’s procurement practices. He recommended establishing a purchasing board that would be responsible to the minister of finance. King tabled the report in the House of Commons on 16 Jan. 1939. In the subsequent debate the opposition fiercely attacked Mackenzie over inconsistencies between the commission’s findings and some of his previous statements. He responded vigorously, claiming to be the victim of “the most unfair attack in British Parliamentary history” (Daily Colonist, 10 Feb. 1939), but lost ground during the resulting uproar. Even the staunchly Liberal Winnipeg Free Press called his defence “weak and inadequate” (11 Feb. 1939) and implied that he should resign. More importantly, King was upset that Mackenzie spoke while under the influence of alcohol. Although King believed that Mackenzie had been “thoroughly honest throughout” and that there was “nothing in the talk of patronage,” he felt his colleague had been “far too provocative” in the house and had “aroused an antagonism” that would “pursue him relentlessly and possibly down him in the end.”

Unrepentant, Mackenzie admitted at the 1939 meeting of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association, held in Vancouver, that defence contracts were by definition politically controversial. He promised that henceforth the Defence Purchasing Board would limit profits and exercise “great responsibility.” He now also warned that Canada’s safety depended upon its ability to supply the varied and complex needs of modern warfare. These assertions did not end the matter. The Financial Post sent Irwin on a fact-finding tour of the country with “no instructions other than to get rid of Mackenzie.” One informant was Major-General Andrew George Latta McNaughton*, former chief of the general staff of the Canadian army. He described the beleaguered minister as a “lazy rascal” and so stupid that he did not realize he did not control his own department. On 26 August the Financial Post launched a series of weekly articles alleging further maladministration at the defence department; on 9 September, the day before Canada went to war against Nazi Germany, it demanded that Mackenzie be replaced “by a stronger, more experienced, more efficient administrator.”

On 19 September Norman McLeod Rogers* took over from Mackenzie as minister of national defence. Curiously, King considered sending Mackenzie to Japan as Canada’s minister or to Ireland as high commissioner. Instead, as part of a larger cabinet shuffle, he made him minister of pensions and national health, which carried with it responsibility for civil air-raid precautions. King had come to doubt Mackenzie, whose drinking had increasingly become a liability. “The truth is,” the prime minister had recorded the day before the shuffle, “Mackenzie is not an administrator. His fort[e] is platform ability, etc.… Had Mackenzie been an abstainer, he might have been in line for the leadership of the Party.” In person, he told Mackenzie that he “needed a change … to save his future.” Mackenzie blamed Deputy Minister Léo Richer La Flèche* for not keeping him informed. This claim may have been retribution for an earlier slight: in 1930, as dominion president of the Canadian Legion of the British Empire Service League, La Flèche had lobbied to ensure that Mackenzie would not be appointed to Pensions and National Health on the grounds that he had a poor record as the official soldiers’ adviser in Vancouver. King saw fault on both sides and was relieved when a physically exhausted Mackenzie announced that he was going to the Homestead resort in Hot Springs, Va, “for a rest and change.”

Upon his return from his southern retreat, Mackenzie quickly embarked on constructive policy work at his new department, which had been set up in 1928 as the successor to the ten-year-old Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment [see Frederick McKelvey Bell*; Sir James Alexander Lougheed*]. He had entered politics as an advocate for veterans, and now that he was in charge of federal policy concerning them, he seized the opportunity to right wrongs and to plan effectively for a new ex-service generation. At his urging, a cabinet committee on demobilization was established on 8 Dec. 1939 and he was named convener. Having lived through the social and economic upheaval at the end of the Great War and having witnessed the disillusionment of many veterans, he understood the need for post-war planning. Thanks to his considerable efforts, as mobilization gathered momentum, Canada was already planning for the return of peace.

During the campaign preceding the 26 March 1940 general election, whenever Mackenzie was questioned about his long absence from British Columbia, he cited the pressure of wartime business. He denied wrongdoing in the Bren gun affair and boasted that the manufacturing contract would be filled ahead of time. He attacked the Conservatives (running as the National Government Party) for undermining national unity. While emphasizing his opposition to conscription for overseas military service, he condemned the CCF for its stance against sending Canadian volunteers to fight in Europe. In speeches delivered in early March and reported in the Vancouver papers, he had much to say about what he envisioned for post-conflict Canada. “We must win the war,” he cautioned, but “for a purpose. And that purpose is the betterment of the standard of life of the Canadian people.” After the war, he contended, there would have to be fundamental change in the financial system of the country. Speaking in his home province, he praised King for being a “left-wing Liberal,” as shown by his commitment to the unemployment-insurance plan now in the works. When a heckler shouted that he should not refer to George Drew only by his surname but as Mr Drew or Colonel Drew, the quick-witted Mackenzie switched to calling his Ontario nemesis General Drew and described him as “unscrupulous” (Sun, 11 March 1940). On election day the Liberals rolled up the biggest majority achieved in Canada to that time. Mackenzie himself had a comfortable win in Vancouver Centre: 12,100 votes, compared with 9,338 for the National Government Party candidate and 8,427 for the CCF candidate. But with the Financial Post and Maclean’s still targeting him, victory in “the battle of the Bren gun,” as the Province called it the day after the election, proved elusive. Early in 1941, while Mackenzie was absent, the cabinet would cancel the original contract and approve two new ones to provide for expanded production. Mackenzie feared a revival of the controversies and issued a face-saving statement stressing the “highly efficient” management of the first contract and claiming that the two now in its place merely simplified accounting and administration. Yet he bitterly told Clarence Decatur Howe*, whose Department of Munitions and Supply had arranged the deals, that the words “cancel” and “cancellation” were a personal affront.

Mackenzie’s involvement in British Columbia politics changed dramatically in 1941. In January premiers Pattullo, Hepburn, and William Aberhart of Alberta walked out of the dominion–provincial conference, which had been called to discuss the report of the royal commission on dominion–provincial relations [see Newton Wesley Rowell; Joseph Sirois]. Mackenzie vigorously defended the document. He believed that action on the commission’s call to restructure confederation to bring constitutional responsibilities into line with fiscal capacity was essential to creating a social-welfare state. For their part, the dissident premiers objected to the commission’s recommendation that Ottawa equalize services across the country, which, they argued, would compel the “have” provinces to subsidize the “have-nots.” In the 11 Oct. 1941 election Pattullo’s Liberals secured only 21 of 48 seats. Mackenzie neither participated in the campaign nor attended the subsequent provincial Liberal convention at which delegates deposed Pattullo as party leader and then voted to form a coalition government with the Conservatives, who had 12 seats. Mackenzie hated coalitions, but he preferred this option to the possibility of the socialist CCF, the official opposition with 14 seats, slipping into power. Once the new government was securely in place under the leadership of John Hart*, Mackenzie became less involved with British Columbia politics, but he remained vigilant in defending provincial interests.

On occasion Mackenzie’s focus on departmental responsibilities directly affected his constituency. For example, he chastised Vancouver’s municipal government for not doing enough to follow air-raid precautions. What stirred greater controversy was his department’s order that the Greater Vancouver Water District chlorinate its water because it contained impurities that exceeded the standard required by foreign ships calling at the port. He took credit for securing shipbuilding and other munitions contracts for the province but could not persuade his cabinet colleague Howe or private investors that it was practical to manufacture steel on the west coast. Nor could he convince Howe that the federal government should engage in merchant shipping so that British Columbia producers could export lumber to Britain at competitive prices. Reviving his old interest in extending railways, he encouraged Premier Hart to make a case to Ottawa that connected the handicap of high transportation costs with the need for a link between the population centres of the south and the Peace River district.

Inevitably, as British Columbia’s representative in the cabinet, Mackenzie had a key role in decision making about Japanese Canadians following Japan’s surprise attack on the American base at Pearl Harbor and Canada’s declaration of war against Japan on 7 Dec. 1941. At the time there were 22,096 Japanese among British Columbia’s 817,861 residents. In mid January 1942 Mackenzie chaired a meeting that brought together provincial and federal officials to discuss the situation of the Japanese in Canada, especially the approximately 3,000 male nationals of military age. To avoid what he termed “unwise tactics” by the Caucasian majority, Mackenzie recommended the immediate transfer of all Japanese men, including those who were Canadian nationals by birth or naturalization, to the interior of the province to work on road construction. King accepted much of the advice, announcing that Japanese men would be moved inland and could volunteer for a civilian labour corps. This briefly eased matters, but as Japan’s armed forces sped towards Singapore, British Columbians increasingly demanded the removal from the coastal zone of all people of Japanese ancestry. On 23 Feb. 1942 Mackenzie relayed to cabinet members Premier Hart’s report that feeling was “simply aflame” in the province, along with the news that representatives of Vancouver’s business elite were organizing a citizens’ defence committee. Mackenzie feared an “outburst.” The next day, in the interest of maintaining law and order, the cabinet agreed to move all Japanese inland. The decision was widely welcomed in British Columbia and won plaudits for Mackenzie. The week before, William Bruce Hutchison* had reported in the Victoria Daily Times (16 Feb. 1942) that almost alone Mackenzie had “carried British Columbia’s fight for action on the Japanese problem.” Many historians, in step with Hutchison, have underplayed the fact that Mackenzie was responding to pressure from city councils, service clubs, political organizations, individual voters, and most of the province’s mps. There was pressure from senior cabinet colleagues as well. In fact, as the Toronto Daily Star reported on 23 February, Minister of Justice Louis-Stephen St‑Laurent* had recently told members of the Canadian Bar Association’s Ontario section that the presence in British Columbia of a large number of naturalized and Canadian-born Japanese required “something more drastic and widespread than what has been done so far.”

Delays in sending the Japanese inland caused further dissatisfaction in the province, especially in Vancouver, where many of them were temporarily housed at the Pacific National Exhibition grounds. Mackenzie promised that as long as he was in public life he would see to it that the Japanese never returned to the coast. He would repeat this statement on a number of occasions, most notably to the 1944 dominion convention of the Canadian Legion. Much to King’s consternation, Mackenzie and many other British Columbia mps refused to retreat from their stand on the issue, which remained popular in coastal British Columbia and would prevent the Japanese from going back to the coast until 31 March 1949. As part of his long-term agenda of exclusion, Mackenzie strongly favoured the sale of all Japanese property by the Custodian of Enemy Property, the federal agency responsible for administering the assets of those moved inland. He was especially anxious to have Japanese-owned farms in the Fraser valley purchased for use by veterans. The Globe and Mail and other publications criticized government administrators for charging veterans significantly more for the land than Ottawa had paid for it. These claims angered Mackenzie, but he accepted the Globe’s explanation that it was attacking the policy, not him. After the war there was concern about injustice to the former Japanese owners, and Henry Irvine Bird, who was serving on the British Columbia Court of Appeal, was appointed to a one-man federal royal commission to examine claims and recommend adjustments in cases where the custodian had not bought properties at fair market value. The government did pay some compensation. In addition, in response to pressure from civil-liberties groups and others, Ottawa eventually abandoned “voluntary repatriation” (deportation) to Japan, a policy favoured by Mackenzie, but not until almost 4,000 people had been sent to Japan.

On the war’s most divisive national issue – conscription of men for overseas service – Mackenzie remained loyal to the prime minister. Still a reserve officer, he had tried to enlist in June 1940 at age 49, but high blood pressure made him ineligible for active service. In a parliamentary speech on 6 Feb. 1942 he supported the government’s decision to hold a plebiscite to seek release from its promise not to conscript men for service abroad. Describing himself as “a Scottish-Canadian,” he praised “the courage and patriotism” of his French Canadian colleagues but made it plain that the government should be free to act as the needs of the war dictated. Claiming that the upcoming plebiscite was a non-partisan matter, he asked a local organizer to work with the Conservatives and the CCF to get out the vote. The plebiscite on 27 April did not settle the issue. English Canada voted overwhelmingly in favour of releasing the government from its pledge, but French Canada voted overwhelmingly against it. A month later Mackenzie, speaking as an individual, told a Canadian Legion audience that if he could have his way “the first conscript in Canada would be money.” Following the 6 June 1944 D-Day landings in Normandy, France, the shortage of troops would become acute. He supported Minister of National Defence James Layton Ralston’s position that conscripts should be sent overseas to meet the needs of the Canadian army on the battlefield.

Throughout the war years Mackenzie also pushed hard for social-security measures, especially health insurance, for all Canadians. In July 1941, the month after he was made a commander of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, Saturday Night magazine (Toronto) praised his speeches on social policy, observing that he had struck “an entirely new note.” Owing to Mackenzie’s initiative, on 2 September the government appointed an advisory committee on reconstruction and re-establishment. Made up of experts outside of government, it was headed by McGill University principal Frank Cyril James*. The James committee in turn commissioned Leonard Charles Marsh*, who had studied with William Henry Beveridge at the London School of Economics and Political Science, to examine the issue of social security for Canada. In a national radio broadcast on 16 September, Mackenzie reasserted that the country would “not tolerate a return to depression-era conditions”; Canadians serving overseas must come back to a “better – finer – stronger – healthier – homeland.” On 24 March 1942, on Mackenzie’s motion, the House of Commons appointed a special committee on reconstruction and re-establishment, on which he served. Led by mp James Gray Turgeon, its task was to oversee plans for the transition to peacetime.

Mackenzie instructed his officials to study both Beveridge’s celebrated 1942 report on social security for Britain and New Zealand’s social-welfare program and make recommendations on their adaptation for Canada. On 4 December in Ottawa he opened a general conference on reconstruction, sponsored by the advisory committee headed by James, and the following March he submitted to the special committee a comprehensive policy statement. He likewise presented to the newly created special committee on social security, of which he was also a member, Marsh’s report on social security and draft legislation – the handiwork of physician John Joseph Heagerty – for a scheme of national health insurance. Mackenzie stressed the idea that, while coverage would be universal, compulsory premiums would prevent the creation of a “pauper mentality” and counteract the belief that the public purse was bottomless. He warmly welcomed Marsh’s recommendations for a comprehensive Canadian welfare state but cautioned that social security “must never be regarded as an anaesthetic against industry, activity, initiative and hard work.” This mixture of radicalism and conservatism was typical of him. With the CCF a growing political threat, he told an Ontario Liberal convention, “Our new world will be based on controlled enterprise rather than on unrestricted enterprise.… Remember that socialism means collectivism, bureaucracy, and the end of personal liberty or personal enterprise.” In contrast, the Liberal Party was “relentlessly going forward from reform to reform and breaking down the walls of privilege” (Globe and Mail, Toronto, 30 April 1943). As he saw it, the future lay in a welfare state within the framework of the market economy.

At Mackenzie’s invitation Beveridge came to Ottawa in May 1943 to testify before the House of Commons special committee on social security. Mackenzie succeeded in getting the committee to give general approval to the health-insurance plan. He was, however, unable to overcome cabinet colleagues’ worries about costs and failed in his attempt to set up a dominion–provincial conference to clear the constitutional and financial way for health-care legislation. A 1944 gathering of provincial ministers of health was the next-best option. Responsibility passed into other hands soon after, when Mackenzie took up his subsequent portfolio. Although publicly funded health insurance would not become a reality until the 1960s, political scientist Malcolm Gordon Taylor credited Mackenzie and his officials with “producing a conceptual design for federal–provincial cooperation, draft legislation, cost estimates, assurances of professional cooperation, provincial government interest and study, and a much better-informed public opinion.”

Thanks to the work of the cabinet committee on demobilization, progress had similarly proceeded apace on post-war planning for veterans. The Post-Discharge Re-Establishment Order (P.C. 7633) came into effect on 1 Oct. 1941, marking a big step towards a comprehensive rehabilitation program for the men and women in uniform. Under this order war service counted towards unemployment insurance, benefits were provided for veterans seeking work or awaiting returns from agriculture or other enterprises, and a variety of grants were introduced for education and technical training. Mackenzie boasted that Canada was the first country in the world to adopt such a comprehensive demobilization plan. In 1942 the order was supplemented by the Veterans’ Land Act and the Reinstatement in Civil Employment Act. Two years later Mackenzie’s department would publish the first of several editions of the pocket-sized booklet Back to civil life, which explained to veterans the government’s evolving program. Mackenzie’s preface succinctly summarized the objective: “Canada’s rehabilitation belief is that the answer to civil re-establishment is a job, and the answer to a job is fitness and training for that job.” The Department of Finance insisted that more must be done to ensure that all who had served would receive help, and it recommended that the entire benefits package be called a veterans’ charter, similar in concept to the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (known as the G.I. Bill of Rights) in the United States. In response the Canadian government devised the War Service Grants Act of August 1944. It provided entitlements rather than discretionary benefits: a gratuity (a cash grant based on duration and location of service) and a re-establishment credit (against which a veteran could submit bills for specified re-establishment purposes). Mackenzie and Ralston guided the measure, expected to cost $750 million, through the House of Commons, and on 18 October Mackenzie became Canada’s first minister of veterans affairs. Walter Sainsbury Woods*, another Great War veteran and the key figure in administering the benefits, was named his deputy.

Earlier that month Mackenzie had also become the first leader of the government in the House of Commons, a role invented to manage the flow of legislative business. Twice during King’s absence overseas, he served as acting president of the Privy Council, but not completely successfully. On one occasion, under the influence of alcohol, he embarrassed neophyte cabinet minister Paul Joseph James Martin* by joining the opposition in criticizing Martin’s explanation of the king’s printer’s budget.

In the campaign preceding the general election of 11 June 1945, Mackenzie confined his appearances to the Vancouver area. He drew applause for his stand on Japanese Canadians and trumpeted the government’s achievements in social security – unemployment insurance and family allowances (legislated in 1944) – by saying that they accorded with his “chief lifelong purpose in public service.” On 23 May the Sun quoted his ridiculing of the Conservatives as the party of “disgruntled major-generals.” Speaking from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Vancouver radio station, he repudiated a CCF allegation that the Liberals would end war-service gratuities, recalling that when King had urged Canadians to stand at Britain’s side, the CCF had declared that Canada should not send an expeditionary force but then argued the opposite after Germany attacked the Soviet Union. He welcomed the containment of the CCF in the Ontario election on 4 June 1945, signalling as it did for him the end of “the Socialist menace” (Sun, 5 June 1945) in Canada. He challenged George Drew, premier of Ontario since 1943, to explain the Progressive Conservative alliance with the anti-war faction in Quebec, his anti-western attitude regarding freight rates, and his opposition to family allowances. He also wanted him to make it clear that the Bren gun contract, which Drew had savaged as a journalist, had been successful. In turn, Drew, speaking in Vancouver, labelled Mackenzie a “contemptible liar” and “a complete failure” as a minister, as both the Sun and the Province reported on 7 June. Mackenzie called the 1945 campaign the “toughest fight of his career” (Sun, 12 June); in the end he survived a close three-way battle with the CCF and the Conservatives. Nationally, the Liberals secured a narrow majority, winning 125 of 245 seats.

The end of the war in Europe in May had triggered full implementation of the government’s rehabilitation plans. In July Mackenzie went overseas to visit members of the Canadian forces and explain the benefits program that had been put in place for them. Woods and representatives of the Civil Service Commission undertook a separate mission to recruit personnel for the rapidly expanding Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA). At the Dominion–Provincial Conference on Reconstruction in August, Mackenzie presented the federal plans for veterans, together with a comprehensive social-security program, including health insurance, to be funded jointly by the two levels of government. When the provinces, led by Premier Drew, would not surrender some of their taxation powers, Ottawa’s ambitious plans fell through. Nonetheless Mackenzie remained optimistic that public finances would eventually be reorganized along the lines favoured by the Rowell–Sirois commission and that, one day, his goal of a comprehensive social-welfare state would be realized.

For the moment, his main concern was the heavy administrative load at the DVA as the forces demobilized en masse (395,013 in 1945 and 381,031 in 1946). With Mackenzie’s support, Wilfred Parsons Warner, the department’s director general of treatment services, revolutionized its hospital system and made the operation a model of its kind. On 6 Sept. 1945 the speech from the throne promised the consolidation of the government’s offerings for veterans under an all-inclusive name, the Veterans Charter. Subsequently, Mackenzie was kept busy with the work of the special committee on veterans affairs. Chaired by Saskatchewan mp Walter Adam Tucker*, its reports led to the passing of the Veterans Rehabilitation Act, which Mackenzie shepherded through the house, thus putting into statutory form the program that had been launched in 1941 with the order P.C. 7633. In early January 1946 he complained to King that the DVA faced “a continuous running fight” with other departments because the cabinet had not made it clear “that the claims of veteran rehabilitation are paramount at this time”; nevertheless, the administration of the Veterans Charter went ahead at full steam. That year about 35,000 veterans received assistance that allowed them to attend university; thousands of others were in vocational training, and payments flowed from the package of gratuities and re-establishment credits provided by the War Service Grants Act. As well, the Veterans Charter was rounded out with the Civilian War Pensions and Allowances Act and the Veterans’ Business and Professional Loans Act. In Mackenzie’s opinion, as he would tell the Vancouver Board of Trade in December, Canada had “experienced the most frictionless demobilization of a great army” ever known, notwithstanding a lack of housing. The shortage had been particularly acute in Vancouver, where on 26 Jan. 1946 members of the New Veterans Branch of the Canadian Legion had occupied the old Hotel Vancouver, which the Department of National Defence had previously used as offices and barracks. Mackenzie got the parties involved to agree to let the hotel continue as a hostel for veterans and their families until new dwellings could be built.

On 8 February, to mark the 25th anniversary of his first election as a “wild young man” (Sun, 9 Feb. 1946), Mackenzie was celebrated at a spirited dinner hosted by the Vancouver Laurier Club. The ebullient politician revelled in this sort of bonhomie. But he could be impulsive, obstreperous, and jealous, which strained some of his relationships. At the beginning of the year he had exploded upon hearing that Minister of Justice St‑Laurent and Minister of Finance James Lorimer Ilsley* had been named to the imperial Privy Council in King George VI’s new year’s honours list. Both colleagues were his junior in service and appointment, so he perceived a deliberate insult and told King he was quitting. The prime minister calmed him, but another dust-up followed in May when Howe was also made a member of the council. This time Mackenzie sent a letter of resignation to King, who was in London, and he complicated the situation by proposing to announce the decision himself rather than let the prime minister do so, as was standard practice. Again King smoothed over the crisis, attributing Mackenzie’s latest outburst to his “present condition of health and matters connected with his life.”

When King attended his first caucus meeting after returning from London, Mackenzie made, in the prime minister’s words, “a nice little speech” about how well Ilsley had managed as acting prime minister. He even congratulated Howe on his appointment to the imperial Privy Council. These gestures gave Mackenzie some credit with King, but the prime minister feared more trouble if St‑Laurent were made acting prime minister while King attended the Paris Peace Conference. To ease matters, King hinted to Mackenzie that he would try to have him made a councillor. “After all,” King rationalized in his 9 July diary entry, “he is the oldest colleague I have and has perhaps done more than the others toward furthering [the] social programme that has helped us to carry the elections. He has certainly shown a very fine spirit since my return. Quite a different man. What a curse drink is.” In December, as part of a cabinet shuffle, King contemplated making Mackenzie secretary of state, but in a telephone conversation about this possibility Mackenzie flew into a rage, saying he regarded it as a demotion. King reminded him that he had requested the change because of his health, but Mackenzie insisted that he was much better and the veterans wanted him as minister. King let him continue in his portfolio for the time being and announced that Mackenzie’s long-desired imperial Privy Council distinction would appear in the king’s new year’s honours list for 1947. On the day before King broke the news Mackenzie had proposed himself for the chairmanship of the International Joint Commission, but nothing came of this initiative.

During the summer of 1947 Mackenzie’s personal life suddenly changed course when, at age 57, he became engaged to 26-year-old Helen Mary MacRae of Winnipeg (the report of an engagement more than a decade earlier had been ill-founded). Her sister, Elizabeth Morton, was the wife of John Kennedy Matheson, a member of the Canadian Pension Commission and an old friend of Mackenzie’s from Vancouver. When the prime minister met the bride-to-be the week before the wedding, he privately told her she “was pretty brave in undertaking to look after Ian.” She responded that Mackenzie had promised to give up drinking. Still, King confessed in his diary that he foresaw “tragedy” in the making; a few weeks before, he had expressed fear that his mercurial minister was “going fairly rapidly to pieces.” The nuptials took place on 10 September at the Matheson home in Ottawa. The newly-weds settled into the groom’s suite at the Mayfair Apartments, an upper-class residence at 260 Metcalfe Street. King’s gift to them was a picture of himself with his dog, Pat. By January 1948, with Mackenzie said to be spending and imbibing freely, King decided that, despite the risk of losing a seat in a tight parliamentary situation, he must shuffle the troublesome minister to the Senate. St‑Laurent, King’s chosen successor, made it plain that he did not want Mackenzie in any cabinet he might form. At a stiff interview on 14 January, King told Mackenzie that “a life appointment in the Senate was really in the nature of a reward for a long public service.” Warning that a man could break down or suffer long illness, he pressed Mackenzie to seize the offer of the seat, especially because of what he owed his young wife, and urged him to leave behind “active politics in the House,” with its “associations and temptations.” After considering the matter for 24 hours and scrambling to meet the constitutional property requirement for senators (he did not own property in British Columbia), Mackenzie accepted. On 19 January he resigned from the cabinet and moved to the Red Chamber. At his final cabinet meeting, he thanked his colleagues for their consideration and expressed regret at leaving. But, King noted, “no other member of Council said anything.”

On 26 April 1948 Mackenzie, as senator, introduced his last bill, which coincidentally brought him back to his origins in Canadian politics: it provided for the incorporation of the Canadian Legion. On 2 July his alma mater, the University of Edinburgh, awarded him an honorary degree and lauded him for having produced a training program for veterans that was “calculated to save the Canadian professions and Canadian leadership in all walks of life from the loss of a whole generation.” Early in 1949 he resumed the practice of law in Vancouver in partnership with Albert Gilbert Duncan Crux (Mackenzie had been made a kc in 1937). While he and Helen were in Banff, Alta, so that he could attend the annual meeting of the Canadian Bar Association, Mackenzie, who had a history of heart trouble, suffered a cardiac seizure. He died a few days later, on 2 September, at the age of 59. In his last will and testament, made in Ottawa on 28 Sept. 1947, he had requested “a very simple service … conducted in part in the Gaelic language.” King noted in his diary that it had been Mackenzie’s wish to be buried in his homeland, but after the funeral on 6 September at Vancouver’s Central Presbyterian Church, his remains were interred at Ocean View Burial Park as the pipe major of the Seaforth Highlanders played Lochaber no more. Later, his name (spelled Ian Alasdair), age, and the month, year, and place of death would be inscribed on the family monument in the Stoer Cemetery in Scotland. Mackenzie left his estate, valued at $56,581.40, with debts of $2,667.59, to his wife, with the proviso that she give some of his books to his youngest sister. He did not name an executor, but Helen was granted probate. In December she arranged to deposit a collection of his papers in the Public Archives of Canada. She also gave King a pair of gold cufflinks that had belonged to her husband. These were inscribed with his initials and the Mackenzie coat of arms.

Ian Mackenzie was an ambitious and energetic man who, from humble beginnings, went far in life in a new country. He was outgoing, gallant, and a born raconteur who “loved the sound of words, the music of language.” As a proud and sentimental Highland Scot, “he delighted, in the company of friends, to slip into Gaelic and beguile his listeners with sonorous passages from the literature of his own, his beloved, his never-forgotten native land” (Province, 2 Sept. 1949). At a Liberal meeting in Cape Breton North and Victoria in 1937 he had recalled that many of the early settlers there were from his own county of Sutherland, some from his parish of Assynt, and he gave the last five minutes of his speech in Gaelic, which over half of the audience understood.

In public life Mackenzie was a man of strong opinions, all vociferously expressed. With a gift for the style of platform oratory popular in his time, during the 1930s and 1940s he was a determined advocate for a regulated and reformed market economy and a social-welfare state. He was a firm believer in the British connection and an ardent defender of Canadian autonomy, combining all these convictions with a progressive view of the role of the state in modern conditions and extolling the Liberal Party of Canada as “the great Centre party, setting a straight and steady course between the extremes of Reaction and Revolution.”

Mackenzie was also outspokenly ethnocentric. Though an immigrant himself, he believed in what he told a gathering of Presbyterian leaders in October 1947 was “a duty to preserve the homogenous character of the Canadian people.” Immigrants “of various races and nationalities” should not, in his opinion, be allowed “to overwhelm our native culture.” That he is mainly remembered for his hard policy concerning Japanese Canadians is not surprising: his advocacy of “No Japanese from the Rockies to the sea” encouraged actions that went well beyond the exigencies of war, and his policy was widely supported in British Columbia during this time. In the case of Japanese Canadians, Mackenzie promoted both exclusion and expulsion. Ironically, in May 1947 he was called upon to move a resolution in the House of Commons in favour of establishing a joint committee with the Senate to consider “the question of human rights and fundamental freedoms” in Canada in the context of the charter of the United Nations and the work of that organization’s commission on human rights.

According to a sympathetic article in Western Business and Industry that same month, Mackenzie’s weaknesses had been played up and his virtues played down. A man with a reputation for joie de vivre and “hearty tastes,” he was also known for his “conscientiousness and sincere record of public service.” Unquestionably, his penchant for alcohol and freewheeling way of life adversely affected his career and compromised his health, but his accomplishments deserve to be remembered along with faults and failings. His most notable achievement was the Veterans Charter, which facilitated a relatively smooth transition to peacetime conditions after World War II. The contrast with demobilization and its messy and disruptive aftermath following the Great War was striking. Though the health-insurance scheme he pushed went nowhere, his initiatives hold an important place in the early history of Medicare in Canada, a program that he did not live to see. King said much about a complex personality when, after hearing of Mackenzie’s death, he mused, “I spent most of the morning writing out a tribute to his memory, – trying to be sincere, overlooking as one does of those who have passed away, all that I knew and felt of his wrongs to himself & others, & giving such praise as I honestly could.”

The Ian Mackenzie fonds (R4742-0-1) at Library and Arch. Can. in Ottawa contains information about Mackenzie’s early life and covers in detail his career from 1930 until his death. The correspondence and diaries of William Lyon Mackenzie King (R10383-0-6), also at Library and Arch. Can., include much correspondence with Mackenzie as well as the comments of the prime minister and others about him; the digitized diaries are available at www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/prime-ministers/william-lyon-mackenzie-king/Pages/diaries-william-lyon-mackenzie-king.aspx (consulted 29 May 2018). The papers of some of Mackenzie’s contemporaries provide insights into his career as a member of the provincial legislature and later as the province’s representative in the federal cabinet: those of his long-time secretary are in the Charles Norman Senior fonds (PR-0211), housed at the B.C. Arch. in Victoria, and those of the Farris brothers, Wendell Burpee (RBSC-ARC-1186) and John Wallace de Beque (RBSC-ARC-1185 and RBSC-ARC-1760, files 1-01 and 1-02), both prominent Liberals, are located in Rare Books and Special Coll. at the Library of the Univ. of B.C. in Vancouver. Because British Columbia’s legislature did not publish a record of its debates during the years that Mackenzie was active in politics, the province’s main metropolitan newspapers are invaluable for documenting his time as an mla. The Conservative newspapers, the Vancouver Daily Province and Victoria’s Daily Colonist, and the Liberal papers, the Victoria Daily Times and Vancouver Sun, also provide context and comment for his work as an mp.

Mackenzie has not been the subject of a book-length biography, but he is mentioned in the published biographies and memoirs of his contemporaries. Of special note is R. MacG. Dawson and H. B. Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King: a political biography (3v., Toronto, 1958–76), 3. Mackenzie appears in passing in J. T. Saywell, “Just call me Mitch”: the life of Mitchell F. Hepburn (Toronto, 1991); J. W. Pickersgill, My years with Louis St. Laurent: a political memoir (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1975); P. [J. J.] Martin, A very public life (2v., Ottawa, 1983–85), 1 (Far from home, 1983); and A party politician: the memoirs of Chubby Power, ed. Norman Ward (Toronto, 1966).

Several major incidents and themes in his career are covered in articles and books. On the Bren gun affair, see two definitive works by David MacKenzie: “The Bren gun scandal and the Maclean Publishing Company’s investigation of Canadian defence contracts, 1938–1940,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 26 (1991), no.3: 140–62; and Arthur Irwin: a biography (Toronto and Buffalo, 1993). Mackenzie’s role in shaping wartime policy regarding Japanese Canadians is treated very critically in Ann Gomer Sunahara, The politics of racism: the uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War (Toronto, 1981). His involvement is set in a broader context in P. E. Roy, The triumph of citizenship: the Japanese and Chinese in Canada, 1941–67 (Vancouver and Toronto, 2007). Mackenzie’s work in the making of the Veterans Charter is surveyed in Peter Neary, On to Civvy Street: Canada’s rehabilitation program for veterans of the Second World War (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2011). A. F. Cross offers an interesting assessment of Mackenzie’s personality in “Criticism has veiled a brilliant Scot,” Western Business and Industry (Vancouver), 21, no.5 (May 1947): 65–69. Among other sources relating to Mackenzie’s efforts for health insurance are Making medicare: new perspectives on the history of medicare in Canada, ed. G. P. Marchildon (Toronto and Buffalo, 2012); C. D. Naylor, Private practice, public payment: Canadian medicine and the politics of health insurance, 1911–1966 (Montreal and Kingston, 1986); and M. G. Taylor, Health insurance and Canadian public policy: the seven decisions that created the Canadian health insurance system (Montreal and Kingston, 1978).

Cite This Article

Patricia E. Roy and Peter Neary, “MACKENZIE, IAN ALISTAIR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackenzie_ian_alistair_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackenzie_ian_alistair_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Patricia E. Roy and Peter Neary |

| Title of Article: | MACKENZIE, IAN ALISTAIR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2019 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |