Source: Link

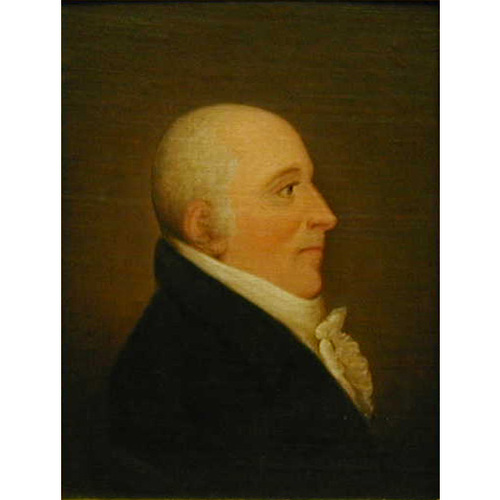

QUESNEL, JOSEPH, businessman, composer, militia officer, playwright, and poet; b. 15 Nov. 1746 in Saint-Malo, France, third child of Isaac Quesnel de La Rivaudais and Pélagie-Jeanne-Marguerite Duguen; d. 3 July 1809 in Montreal, Lower Canada.

Joseph Quesnel, the son of a prosperous merchant, attended the Collège Saint-Louis in Saint-Malo. When he had finished his studies, he took ship for Pondicherry (India) and visited Madagascar. In 1772 he travelled to French Guiana, the West Indies, and Brazil. After that he took up residence in Bordeaux, France, where he went into partnership with his uncle, Louis-Auguste Quesnel.

In the autumn of 1779 Quesnel embarked on the French privateer Espoir for North America. According to tradition he was in command of this vessel, which was carrying war supplies and munitions to help the American colonies in their revolt against Britain. Whatever the case, the ship was captured off Newfoundland by the Royal Navy and taken to Halifax, N.S. Quesnel avoided imprisonment but had to remain in British North America until the end of hostilities. He arrived in Montreal bearing a safe conduct issued by Governor Haldimand. There, on 10 April 1780, he married Marie-Josephte Deslandes, who also came from Saint-Malo but whose mother, Marie-Josephe Le Pellé Lahaye, had come to Montreal after her husband’s death and had married the merchant Maurice-Régis Blondeau.

Quesnel was active in commercial life as Blondeau’s partner. He signed a number of petitions from merchants to the government, including one in 1784 calling for a new constitution and one in 1790 asking for settlement of the problems that Montreal merchants were experiencing because of the lack of a customs office there. Quesnel was also interested in the cultural and social life of his adopted town. In 1780 and 1783 he played in amateur theatrical companies. He is supposed to have composed a piece of music that was performed in public at a Christmas party; he lamented, however, that “they call my music sprightly [and] say it is made for the theatre.” In 1788 he was an ensign, and from 1791 to 1793 second captain, in the local Canadian militia; at the same time he was serving as a churchwarden in the parish of Notre-Dame.

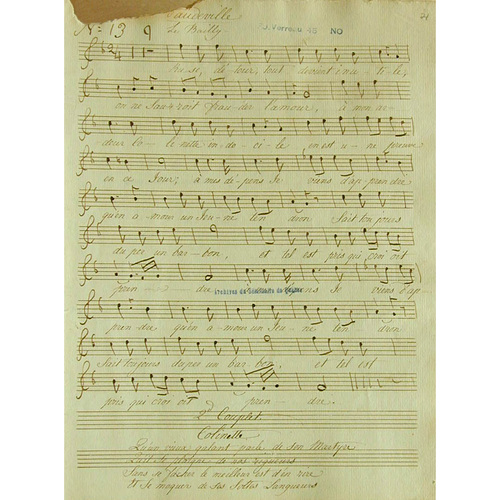

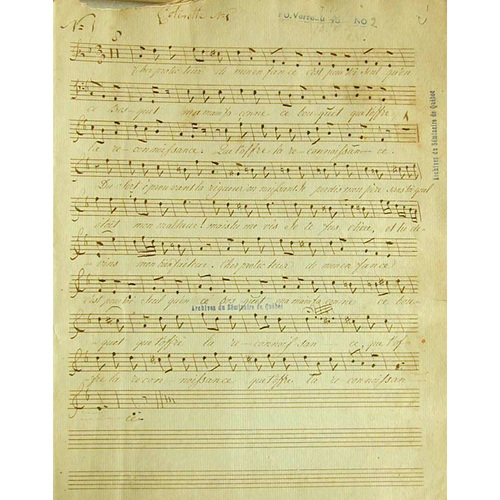

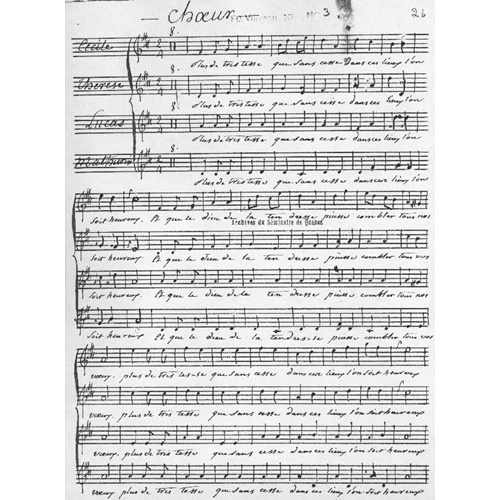

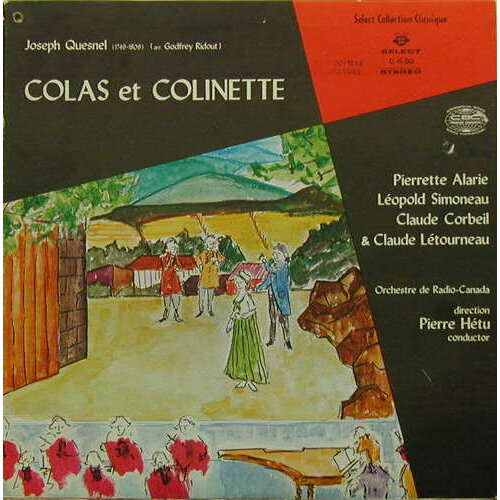

In October 1788 Quesnel had sailed for England; he then spent the winter in Bordeaux. The purpose of his trip was to establish commercial relations with his family in France, particularly with his brother Pierre, who was in business at Bordeaux. Quesnel also took advantage of the voyage to attend theatrical performances. If he had intended to examine the prospects of returning to France for good, the events of the revolution would have put an end to any such hopes. In November 1789, after his return to Montreal, Quesnel founded a theatrical company, the Théâtre de Société, with his friends Louis Dulongpré*, Pierre-Amable De Bonne, Jean-Guillaume De Lisle, Jacques-Clément Herse, Joseph-François Perrault*, and François Rolland. On 11 November Dulongpré undertook to transform his spacious house into a temporary theatre and to supply three stage settings painted on canvas, the lighting, music, wigs, tickets, playbills, caretaker, and ushers. On Sunday 22 November the parish priest of Montreal, François-Xavier Latour-Dézery, preached a vehement sermon denouncing theatrical performances and declared that the church would refuse absolution to those who attended them. At the conclusion of the high mass Quesnel and some of his partners, including De Lisle, protested against this zeal which they termed misdirected. Vicar general Gabriel-Jean Brassier*, who was caught off guard by the firmness of these theatre supporters, all prominent people, wrote to Bishop Hubert* for advice. Hubert censured the conduct of Father Latour-Dézery, by implication acknowledging that his critics were right. The incident was closed in December but a controversy developed in the Montreal Gazette over the morality of the theatre: Quesnel joined in the fray with a long letter published on 7 Jan. 1790 defending both the utility and morality of the theatre. Between 29 Dec. 1789 and 9 Feb. 1790 the company gave four evening performances, producing six plays in all, among them Colas et Colinette, ou le Bailli dupé, a comic opera by Quesnel. The public and the critics acclaimed this comedy in three acts intermixed with 14 songs. In its second season the Théâtre de Société decided to limit the audience “to a very small number of persons of high birth or noble blood”; but an anonymous correspondent questioned the validity of this decision, given the members’ desire to participate in the colony’s cultural development. The new policy may have been dictated by the hostile reaction of the clergy. Whatever the case, the company shut down temporarily.

In 1791 and 1792 Quesnel made several trips to the pays d’en haut. At that period the sale of furs in London was suffering a serious decline and business was becoming difficult. Furthermore, the trading company he had organized in 1790 with five partners, including Blondeau and Pierre Bouthillier, was in trouble. Set up to import Bordeaux wines through his brother Pierre’s firm, the Compagnie Baignoux-Quesnel, it was facing insurmountable difficulties because of stoppages occasioned by the disruptions of the French revolution.

In 1793 Quesnel partially retired from business and went to live in Boucherville, where he had already bought some land. At the turn of the 19th century Boucherville enjoyed a certain reputation as a centre of Canadian social life in the Montreal region. Lord Selkirk [Douglas] noted in 1804 that “the gentry of the place & neighbourhood hold Assemblies of their own at Boucherville . . . where no English intrude.”

Beginning in 1799 Quesnel devoted himself to poetry. His three long poems, written between 1799 and 1805, “L’épître à M. Labadie,” “Le rimeur dépité,” and “La nouvelle Académie,” reveal his wish to make his works known to his friends. He complained bitterly, however, of the lack of attention given them. Quesnel did not publish a collection, but some texts appeared during his lifetime in periodicals; they were either anonymous or else signed with the nom de plume “F” (François). His poetic works consist principally of occasional verse. The charming song “À Boucherville,” composed about 1798, evokes the quiet joys of life long ago. The poetry of this 18th-century man at times took on a philosophical tone. In his first poem, “À M. Panet,” written about 1783 or 1784, he laughs at his friend Pierre-Louis Panet for his faith in Rousseau and Voltaire; he returned to this theme in “Stances marotiques à mon esprit,” composed in 1806. And in “Épître à ma femme,” written the following year, he claims:

Alas! what use is it to regret

The moments of this brief passage!

Death need not sadden us,

’Tis but the journey’s end.

In 1804 he had written his moving “Épître à . . . ,” a farewell to health, pleasures, gaiety, and above all to France which he would see no more.

Quesnel’s concern about his compatriots’ lack of interest in the arts comes out in “L’épître à M. Labadie,” written between 1799 and 1801, in which he repeats Boileau’s plaint: “The saddest occupation is the poet’s trade.” In his long autobiographical poem “Le dépit ridicule, ou le sonnet perdu,” the poet complains to his wife: “What is the good of the trouble I take for rhyming / If no one ever has time to listen to my verse?” His wife, a more practical person, replies: “I see you every day writing or dreaming, / Whilst I must bring up your children.” The poet then announces his great project to her: to invite his friends to a supper, and after carefully double-locking the doors “to read all the lines of my last work.” His concern for interesting his compatriots was still lively when Quesnel dreamed in 1805 of creating an academy of belles-lettres. But it was only a dream, at the end of which woke up “Good old François, / Always musing, absent-minded, full of misanthropy,/ And, especially to fools, unsociable.”

Despite these bitter reflections Quesnel was not ignored by his contemporaries. In January and February 1805 the Théâtre de Société of Quebec performed Colas et Colinette at the Théâtre Patagon. A grateful Quesnel, who was in Quebec at the time, presented the amateur actors with a treatise on dramatic art in verse which had appeared in the Quebec Gazette under the title “Adresse aux jeunes acteurs” and in which his advice, still topical, shows his knowledge and good taste. On this occasion, moreover, Ignace-Michel-Louis-Antoine de Salaberry suggested to the Quebec printer John Neilson* that he publish Quesnel’s dramatic works. In 1807, when Colas et Colinette was again performed, Neilson decided to publish it. However, because of the difficulties he encountered, it appeared without the music and was not put on sale until 1812.

Quesnel was not indifferent to the great problems of his period. As a result of the upheavals of the French revolution which had directly touched his family in France, a cousin having been guillotined and the property of his brother in Bordeaux confiscated, Quesnel openly displayed pro-British sentiments. In 1799 he wrote the poem “Songe agréable” in which he praised the merits of “George the formidable king” who, “Conquering the unconquerable Frenchman, / Will restore peace to the universe.” In 1800 or 1801 Quesnel is believed to have composed a satirical play, Les républicains français, ou la soirée du cabaret, which ridiculed the morals of the heads of local sections in Robespierre’s time. But Quesnel also reacted to the growing influence of the British who had settled in Lower Canada and to their hostile attitude towards the French and the Canadians. In 1803 he responded to the attacks published in an anonymous poem entitled L’anti français. The preceding year he had composed a satirical play, L’anglomanie, ou le diner à l’angloise, in which he ridiculed the infatuation of part of the seigneurial gentry with English fashions. His thinking developed to the point that in December 1806 he published his poem “Les moissonneurs” in Le Canadien, organ of the Canadian party; in it he opposed the pretensions of the British oligarchy in the colony.

Quesnel’s final years were passed serenely in a measure of luxury. In 1808 he was preparing another comic opera, Lucas et Cécile, but he died before it was finished. In the spring he had leapt into the St Lawrence to save a drowning child, and he succumbed to an attack of pleurisy on 3 July 1809 in the Hôtel-Dieu at Montreal. His widow died the following year. The couple had had 13 children, 6 of whom reached adulthood. Their eldest son, Frédéric-Auguste*, who was called to the bar in 1807, used to hold gatherings for the élite in his Montreal home at which his father enjoyed literary conversation. Jules-Maurice* became a fur trader, thus carrying on a family tradition. Joseph-Timoléon practised medicine, and Mélanie married the lawyer and businessman Côme-Séraphin Cherrier*.

A few days after Quesnel’s death Jacques Viger* observed: “It is an irreparable loss for literature and society in this country.” In 1830 Michel Bibaud* paid a stirring tribute to the poet who had been dead for more than 20 years: “There is no Canadian with any sort of education who has not read at least some of the late Mr Joseph Quesnel’s works.” Benjamin Sulte* defined Quesnel’s role very lucidly: “The literary awakening perceptible in our country since 1788 owes most to him.”

Although his writing is at times a pastiche of Boileau, Ronsard, or Molière, Joseph Quesnel remains a writer of the 18th century. His work is interesting primarily for what it reveals of his time, and his special gift was to be able to convey its artistic and literary atmosphere. He proved the most significant French Canadian writer of the period.

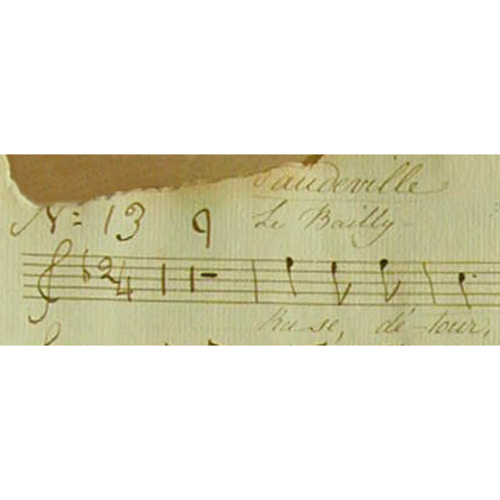

[Works attributed to Joseph Quesnel appeared during his lifetime in various newspapers, including the Quebec Gazette, 7 Feb. 1805; Le Canadien, 29 nov., 13 déc. 1806; 10, 17, 24 janv., 14 févr., 3 oct. 1807; the Montreal Gazette, the British American Register (Quebec), and Le Courier de Quebec. Some were reprinted in Louis Plamondon*, Almanach des dames, pour l’ année 1807 (Quebec, 1807). Colas et Colinette, ou le Bailli dupé (Quebec, 1808) was published by John Neilson; this comic opera was reprinted in the first volume of the Répertoire national, recueil de littérature canadienne, comp. James Huston* (4v., Montreal, 1848–50), which contains six other pieces by Quesnel. Colas et Colinette was also recorded in 1968, the music having been reconstructed by the Toronto composer Godfrey Ridout in 1963. Quesnel’s plays, L’anglomanie, ou le dîner à l’angloise and Les républicains français, ou la soirée du cabaret, were republished in La Barre du jour (Montréal), nos.3–5 (1965): 117–41 and no.25 (été 1970): 64–88, respectively.

The Lande collection (PAC, MG 53, 177) contains 24 manuscript poems by Quesnel, some of which were published in Joseph Quesnel, 1749–1809: selected poems and songs after the manuscripts in the Lande collection, ed. Michael Gnarowski (Montreal, 1970). Jacques Viger’s Saberdache (ASQ, Fonds Viger-Verreau, Sér.O, 095–125) contains the edition he prepared of Quesnel’s texts in 1847. The ASQ also holds the vocal score of Lucas et Cecile (Fonds Viger-Verreau, Carton 45, no.3). Helmut Kallmann and John E. Hare are preparing a critical edition of Quesnel’s works from his recently discovered workbook; this publication should include 30 poems, as well as a few titles attributed to him. j.e.h.]

AD, Ille-et-Vilaine (Rennes), État civil, Saint-Malo, 15 nov. 1746. ANQ-M, CE1-51, 10 avril 1780, 4 juill. 1809. Quebec Gazette, 28 Oct. 1790, 25 July 1799, 7 Feb. 1805, 13 July 1809, 19 April 1810. Michel Bibaud, Épîtres, satires, chansons, épigrammes et autres pièces de vers (Montréal, 1830), 46. Baudouin Burger, L’activité théâtrale au Québec (1765–1825) (Montréal, 1974), 199–215. J. [E. ] Hare, Anthologie de la poésie québécoise du XIXe siècle (1790–1890) (Montréal, 1979), 21–35. D. M. Hayne, “Le théâtre de Joseph Quesnel,” Le théâtre canadien français: évolution, témoignages, bibliographie (Montréal, 1976). Helmut Kallmann, A history of music in Canada, 1534–1914 (Toronto, 1960), 62–67, 121–22. Camille Roy, Nos origines littéraires (Québec, 1909), 125–57. Benjamin Sulte, Mélanges d’histoire et de littérature (4v., Ottawa, 1876), 3: 295. Michel Bibaud, “Littérature,” La Bibliothèque canadienne (Montréal), 2 (1825), no.1: 16–17. Yves Chartier, “La reconstitution musicale de Colas et Colinette de Joseph Quesnel,” Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française, Bull. (Ottawa), 2 (1971–72), no.2: 11–14. J. E. Hare, “Joseph Quesnel et l’anglomanie de la classe seigneuriale. au tournant du xixe siècle,” Co-Incidences (Ottawa), 6 (1976): 23–31; “Le Théâtre de société à Montréal, 1789–1791,” Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française, Bull., 16 (1977–78), no.2: 22–26. É.-Z. Massicotte, “La famille du poète Quesnel,” BRH, 23 (1917): 339–42.

Cite This Article

John E. Hare, “QUESNEL, JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/quesnel_joseph_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/quesnel_joseph_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | John E. Hare |

| Title of Article: | QUESNEL, JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | September 18, 2024 |